All signs point to a meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden during the Apec forum in San Francisco in two weeks. But Beijing has yet to officially confirm Xi’s attendance, a delay reflecting the dismal level of bilateral trust, Beijing’s political culture, concern that Xi could be embarrassed by last-minute events and a bid to extract concessions, analysts said.

Factors behind the hesitancy, analysts and a People’s Republic of China official said, include Beijing’s bid to extract a promise that Washington will not announce new sanctions or other awkward developments during the visit.

“The Chinese don’t want their leader to be embarrassed in the run-up to the summit, during his visit to the US, or immediately following the trip,” said Bonnie Glaser, Indo-Pacific managing director with the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

“This undoubtedly includes an expectation that the US will refrain from taking actions, such as adding new PRC entities to control lists or announcing new export controls.”

In 2017, Xi was unsettled when then-president Donald Trump launched – as the two leaders sat down to eat steak and pan-seared fish at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida – a missile strike on Syria, regarded as a US power play for Trump’s impending talks with Xi over North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

However, the White House is unlikely to provide a “no-news” promise given the very different US political system and concern that it would look soft on China heading into the 2024 presidential election, analysts said.

“This is only a matter of timing,” Glaser noted. “The Biden administration is likely to continue implementing policies that are aimed at enhancing US competitiveness.”

The stakes are high for the long-anticipated Xi-Biden meeting on the sidelines of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in San Francisco in mid-November, as both sides try to put a floor under a relationship that has cratered over Taiwan, trade, technology, defence and other issues.

Xi-Biden talks a ‘step closer’ after Wang Yi’s trip, but China still wary

Also influencing the waiting game, analysts said, is China’s desire to keep its options open, allowing a face-saving exit should some last-minute calamity threaten to undercut the image it seeks to project back home of a leader and nation deeply respected on the global stage.

Front of mind is the rapid fallout after the US detected a Chinese surveillance balloon transiting across North America in late January and early February. Its downing angered Beijing and pushed relations further into the deep freeze just before a planned trip to China by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, who cancelled the visit.

Potential minefields now looming on Beijing’s radar include: the recent collision of Chinese and Filipino ships in the contested South China Sea; the reported near-miss between US and Chinese fighter aircraft; the pending Taiwan presidential election; China’s swooning economy and property crisis; and the Israel-Gaza and Ukraine wars.

“There are a bunch of dark clouds that, if I were them, I would probably wait too,” said Jeffrey Moon, a former National Security Council official and founder of the China Moon Strategies consultancy.

“If, for example, the Chinese announce now that Xi will meet Biden at Apec and a spy-balloon-type incident subsequently occurs that forces cancellation of his participation, then US-China relations will be in an even worse position than if the Chinese remained silent for now about the anticipated meeting,” Moon added.

Holding out also potentially improves Beijing’s bargaining position in last-minute negotiations over summit “deliverables” – China still hopes Washington will drop punitive trade sanctions imposed by the Trump administration, likely a long shot – as well as minor protocol details and the staging of events.

“This is pretty typical,” said Zack Cooper, a research fellow with the American Enterprise Institute. “In any negotiation, as it gets down to the wire, you pressure folks to concede on small issues to maximise leverage.”

Added to the mix is Beijing’s political culture, which places inordinate emphasis on stage management, ceremony and control, in a system where the news media is heavily restricted and a premium placed on the prestige of top leaders, prompting officials to triple-check every detail.

In 2006, when Chinese President Hu Jintao visited the White House, it mistakenly announced China’s national anthem as that of the “Republic of China” and a protester shouted at US President George W. Bush to stop Hu from persecuting the Falun Gong, a religious movement banned in China.

And in 1997, when Jiang Zemin travelled to the US, the first Chinese president to visit since the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown, Beijing insisted that Jiang be assigned a dedicated US protocol officer throughout, since the former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping had enjoyed one.

The State Department had discontinued this practice but complied for the Chinese – “not that it was needed or useful”, said Moon, who helped arrange logistics for Jiang’s trip.

“So this level of preparation is not unique,” he noted.

South China Sea: collision takes three-way game of chicken closer to the brink

Asked Friday when Xi might arrive, a senior White House official said that Washington would “leave it to the Chinese side” to decide the timing, given that Beijing often confirms trips by leaders much closer to the date.

China similarly waited until days before September’s Group of 20 meeting in New Delhi to announce that Xi was not attending. Beijing did not explain its decision, but analysts suggested that China sought to avoid highlighting China-India border problems, contributing to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s bid for Global South leadership – or undercutting the impact of any Xi-Biden meeting.

While US presidential summits take time to arrange no matter who is involved, this one is particularly freighted given the level of distrust. Last week’s preparatory visit to Washington by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi followed trips to Beijing by the US secretaries of state, commerce and the treasury, as well as CIA chief William Burns.

“Summit meetings, especially between the US and China, have never been off the cuff,” said Moon, a former US consul in Chungdu. “But what’s unusual in this case is that there are so many trips back and forth for a summit that, as we can see, will have modest results.”

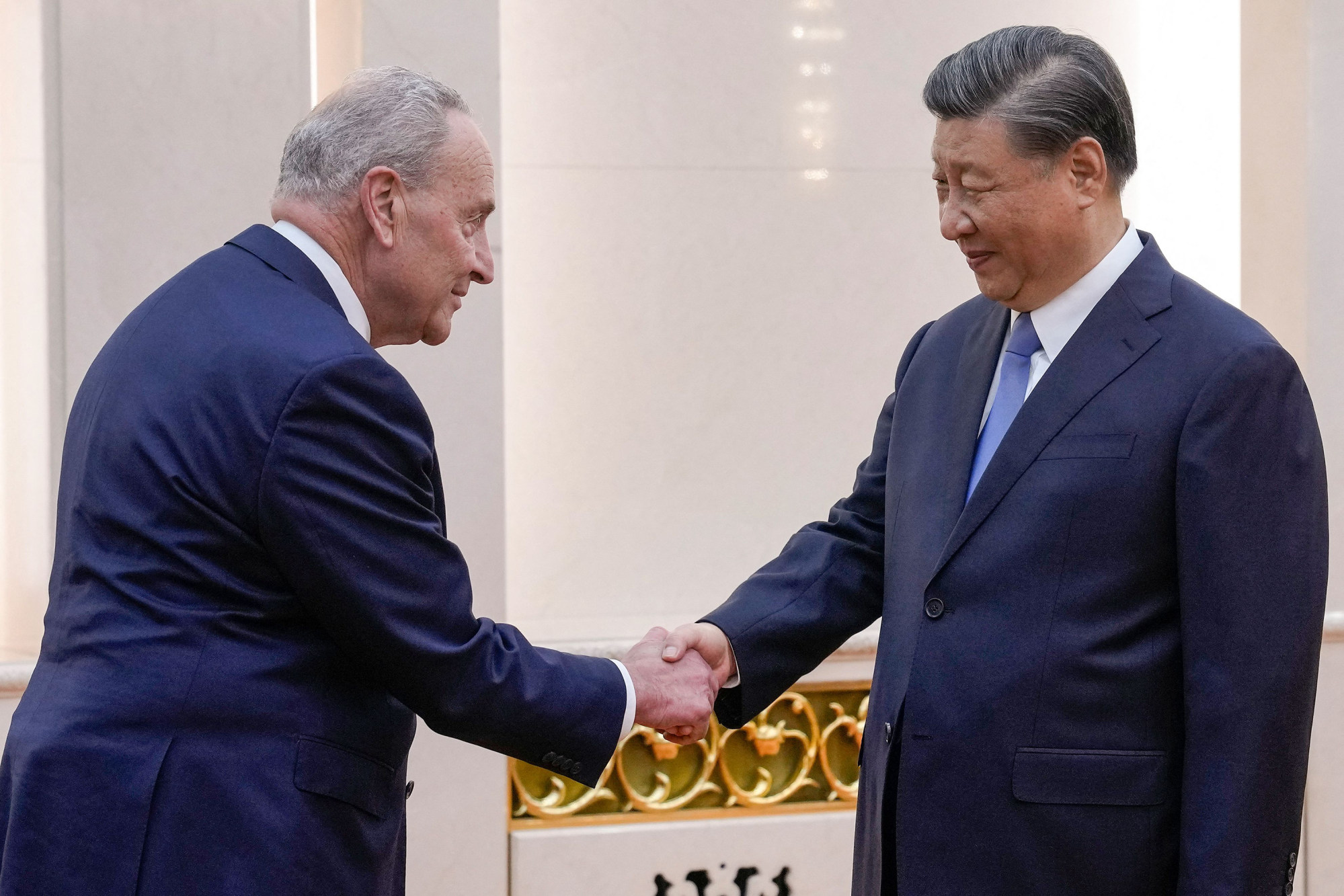

Analysts note that much of the choreography generally seen before a Chinese summit has taken place, including official and unofficial dialogues; in-person meetings; and toned-down rhetoric. Xi, who only selectively meets foreign dignitaries, sat down in Beijing in recent days with California Governor Gavin Newsom and a bipartisan Congressional delegation led by US Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer.

A Chinese official, who was not authorised to speak publicly, argued that Biden could promise to hold off any embarrassing news or disclosures if he wanted to, since cabinet officials report to him.

A former White House official noted that a principled US stance has become more difficult since the actions of Trump, who was known to reach down and interfere in the bureaucracy. This included a decision in May 2018 to reverse regulatory restrictions on Chinese telecommunications company ZTE, allowing it to continue operating.

In the past, bilateral summits promised a road map to improved relations, but the current environment is all about ensuring that things don’t get worse, analysts said.

“That said, stabilising relations is more important than many people realise,” said Moon. “We don’t even pretend we like each other. We’re just trying to find a way to coexist.”

More from South China Morning Post:

- US, China ‘working towards’ Biden-Xi meeting next month on Apec sidelines, White House says

- China, US seeking to set stage for Xi-Biden summit as Economic Working Group holds first meeting

- Chinese envoy uses rough language to describe US relations amid suspicion over Beijing’s intentions

For the latest news from the South China Morning Post download our mobile app. Copyright 2023.