China’s ties with Vietnam are expected to remain largely stable, observers say, even as uncertainty looms in Hanoi following the death of long-serving leader Nguyen Phu Trong.

Trong, 80, who died last week after a long unspecified illness, has left a mixed political and economic legacy after overseeing Vietnam’s rapid economic growth and a “blazing furnace” crackdown on corruption to consolidate the Communist Party’s power.

But observers were generally positive about Hanoi’s pragmatic “bamboo diplomacy” under Trong’s watch – a delicate balancing act between China and the United States amid a deepening rift with its northern neighbour in the South China Sea.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

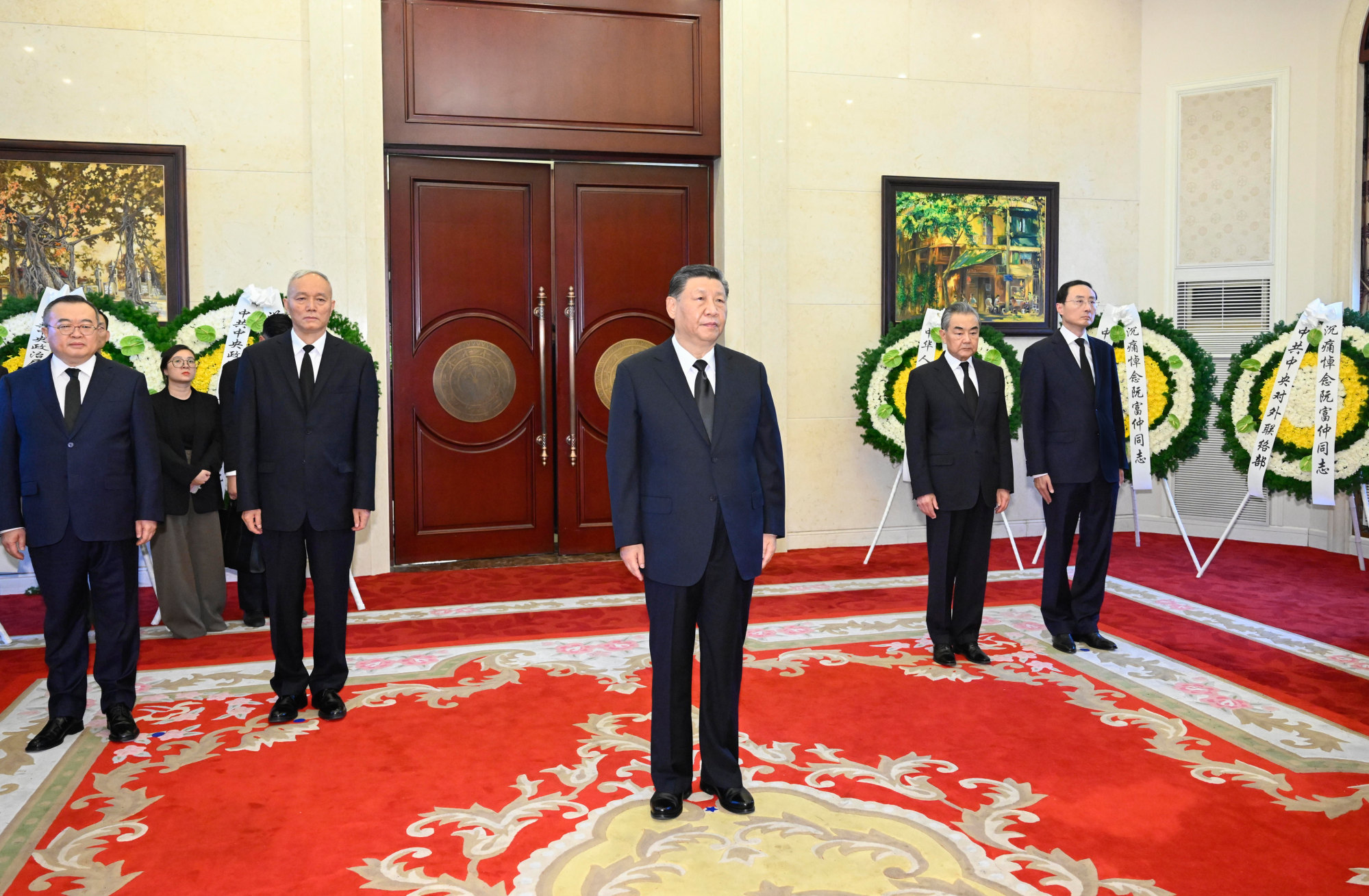

Paying tribute in a rare visit to Vietnam’s embassy in Beijing on Saturday, Chinese President Xi Jinping spoke of their “deep camaraderie” and praised Trong’s “outstanding contribution” to ties between the two countries and their ruling parties.

The Communist Party of China also sent a condolence message hours after Trong’s death was announced, calling him “a good comrade, a good brother and a good friend”. China’s No 4 official, Wang Huning, will lead a delegation to Vietnam to attend Nguyen’s state funeral on Friday.

Hanoi emphasised the importance of its relations with Beijing, with its ambassador to China Pham Sao Mai pledging to “adhere to the strategic choice and top priority of developing friendly cooperation with China”, according to official news agency Xinhua.

Zhang Mingliang, a Southeast Asian affairs specialist at Jinan University in Guangzhou, said Xi’s embassy visit showed Beijing was relatively satisfied with the development of bilateral ties in the Trong era.

“Compared with ties during the oil rig crisis in 2014 and [former US president Donald] Trump’s state visit to Vietnam in 2017, Sino-Vietnamese relations have shown clear improvement, marked by Hanoi’s embrace of the concept of a ‘community of shared destiny’ last year at Beijing’s request,” he said.

“And compared with rancorous tensions with the Philippines in the South China Sea, Vietnam and China have managed to get along without hyping up their deep-seated differences on territorial issues.”

Ties between the communist neighbours had been turbulent in past decades, with clashes over the disputed Paracel Islands in the 1970s and a brief but bloody border war in 1979.

Zhang noted that relations also hit a low point during a 2014 diplomatic stand-off over China’s deployment of a deepwater oil rig near the Paracels, an incident widely seen as a turning point in Hanoi’s ties with Washington.

“Under Trong’s stewardship, Vietnam has managed to forge rather friendly ties with China, at least superficially. But at the same time, Vietnam’s ties with the US and Russia have also been elevated to unprecedented heights,” Zhang said.

“This is all aimed at keeping China in check so that Vietnam can have a favourable international environment and relatively steady ties with China that are largely under Hanoi’s control,” he added. “It may seem like mission impossible but Trong’s Vietnam managed to hedge its bets with the major powers.”

Arguably Vietnam’s most influential leader since its founding revolutionary Ho Chi Minh, Trong became the ruling party’s general secretary in 2011 and secured a precedent-breaking third five-year term in 2021. He also served as Vietnam’s president from 2018 to 2020.

As speculation swirled about his declining health, Trong visited Beijing in October 2022 – his first overseas trip after having a stroke in 2019 – becoming the first foreign leader to meet Xi after he secured his own third term.

Over the past 10 months, Trong hosted both Xi and US President Joe Biden in Hanoi and met Russian President Vladimir Putin in June, despite his frailty. Hanoi has also elevated Japan, India, South Korea and Australia to its top-tier comprehensive strategic partners.

Carl Thayer, emeritus professor at the University of New South Wales in Australia, said Trong would be remembered for his trips to the US and Japan in 2015, which set the foundations for closer ties with the West.

Thayer expected Hanoi’s ties with Beijing to remain “stable and amicable” because Vietnam would not abandon its foreign policy of “peace, cooperation and development”.

“China plays a special role in Vietnam’s foreign relations. It was Vietnam’s first comprehensive strategic partner and it is the only major power to be called a comprehensive strategic cooperative partner,” he said.

Analysts also pointed to Trong’s personal bond with Xi and ties between the two communist parties, which have over the years acted as a ballast in the love-hate relationship between Hanoi and Beijing.

“Although Vietnam broadened its diplomacy and improved ties with the US, I think that Trong was able to assuage Beijing that Vietnam really was neutral and independent and improved ties with Washington would not come at the expense of Beijing,” said Zachary Abuza, a Southeast Asia expert and professor at the National War College in Washington.

“This was possible because of Trong’s committed communist ideology. He viewed the world very much the way Xi Jinping does.”

Abuza also noted China’s party-to-party channels with Vietnam that ensured a constant stream of communication between senior-level officials – a channel unavailable to the US.

According to Nguyen Khac Giang, an analyst at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, there was a close relationship between Trong and Xi due to their shared commitments to Marxism-Leninism.

“This helped stabilise bilateral relations during times of tension, particularly over maritime disputes in the South China Sea,” he said. “Trong also had a very favourable view on China and admired the Chinese Communist Party, although he was pragmatic in dealing with them on many thorny issues.”

Giang said that while Trong’s potential successors – such as President To Lam – do not have this bond with Xi, “I don’t think this will greatly affect Hanoi’s ability to maintain good relations with China as the party-to-party link remains strong”.

He said the bamboo diplomacy approach was “working well” and Trong’s successor was unlikely to change it or his key policies, at least in the medium term “to prove their legitimacy as his rightful heir”.

A day before he died, Trong’s duties were temporarily assigned to Lam. The 66-year-old, who became president in May, was previously Vietnam’s public security minister, overseeing the anti-corruption drive. That campaign has ensnared 40 members of the party’s Central Committee and dozens of military and police generals since 2016.

While the crackdown has been popular with the public, the removal of six out of 18 members of the Politburo since December 2022 – including three of Vietnam’s top five leaders since March – has raised concerns about factional infighting amid fears of a succession crisis.

Despite the political turmoil, Abuza said he expected “absolutely no change” in Vietnam’s foreign policy, with Hanoi remaining “studiously neutral” – with deep economic ties to both China and the US and its allies.

But the new leader could look to make changes on the economic front.

“Like in China, where Xi Jinping has reasserted control at the expense of economic growth, Vietnam did that under Trong, though to a lesser extent,” Abuza said.

“I think the next general secretary will be more pragmatic. Economic growth is the key to the party’s legitimacy. But I expect there to be few changes before the 14th party congress in January 2026. The leadership is consumed with preparations for the party congress and is more or less in a lame-duck session.”

Thayer warned there were limits to personal diplomacy between Chinese and Vietnamese leaders when it came to the South China Sea dispute.

“Personal relationships are important in relations between states ... but they are not sufficient – structure matters,” he said, noting the Steering Committee for Bilateral Relations set up in 2008 that allows senior officials to meet on a regular basis.

He said China refused to respond to nearly 40 hotline calls from Vietnam over several months during the 2014 crisis, despite the personal ties between leaders.

“China only agreed to accept a special envoy from Trong when it learned that angry Vietnamese officials were calling for a special meeting of the Central Committee to exit China’s orbit,” he said.

Thayer said Vietnam’s protest over China sending a hospital ship to the Paracels in May and its move last week to file a claim with the UN for an extended continental shelf in the South China Sea were the “new normal”.

Zhang from Jinan University said the maritime dispute remained one of the biggest variables in bilateral relations.

He said Hanoi’s request to extend the continental shelf beyond the current 200 nautical miles – following a similar move by Manila last month – was likely done under Lam’s watch.

“The timing is intriguing – it was probably aimed at ... demonstrating a tough position on China for the domestic audience while also trying to increase Lam’s bargaining power vis-à-vis China,” Zhang said.

“It showed that Lam, on the one hand, will stick with Trong’s approach in dealing with major powers ... but on the other hand there will be differences, variations and innovative steps,” he said. “While bilateral ties are at a high point ... Vietnam is unlikely to make major compromises with China.”

Meanwhile, Vietnam has accelerated expansion of its outposts in the contested Spratly Islands over the last six months, according to a June report by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies’ Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

It said Vietnam’s overall dredging and landfill in disputed areas of the South China Sea was now roughly half of China’s total of 1,880 hectares (4,650 acres). The total was less than one-tenth of China’s just three years ago.

“It’s just a matter of how long China will put up with Vietnam’s island-building efforts in the South China Sea,” Zhang said.

More from South China Morning Post:

- Vietnam’s Communist Party grapples with succession dilemma after Nguyen Phu Trong’s death

- Vietnam Communist Party chief Trong, 80, dies of ‘old age, serious illness’

- Communist Party of China sends Vietnam condolences on death of leader Nguyen Phu Trong

- Beijing protests after Vietnam asks UN to extend South China Sea continental shelf

- Is Vietnam losing its appeal for China’s manufacturers bypassing US tariffs?

For the latest news from the South China Morning Post download our mobile app. Copyright 2024.