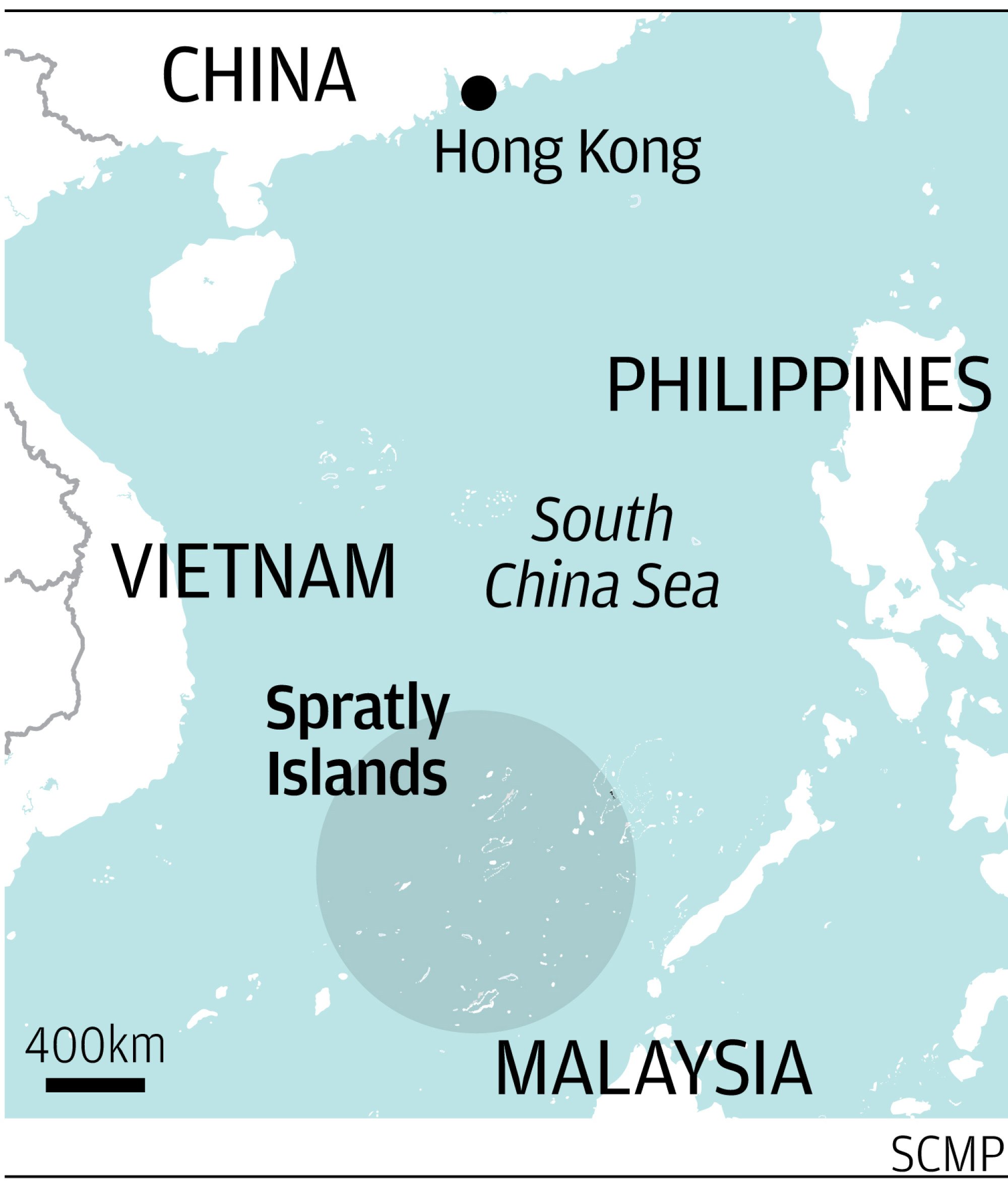

The South China Sea is claimed by almost every country in the region but its ripple effects are felt well beyond the fiercely contested waterway. In the first of a three-part series, Alyssa Chen looks at the differences in China’s response to its maritime disputes with the Philippines and Vietnam.

China’s response to Vietnam’s rapid expansion of its land reclamation in the Spratly Islands has been muted so far – a stark contrast to Beijing’s increasingly assertive response to the Philippines.

While there have been several clashes between Chinese and Philippine vessels around disputed South China Sea reefs in recent months, there are no recorded instances of Beijing trying to stop Vietnam’s activities.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

Analysts said the different approaches were down to a number of factors, including the political relationship between China and Vietnam, the latter’s low-key approach and the alliance between the Philippines and the United States.

But they did not rule out a tougher approach from Beijing in the future and said the issue could still cause problems.

Satellite images published by the Washington-based Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies have shown the unprecedented pace and scale of the land reclamation efforts around the islands and reefs Vietnam controls since 2021.

In May the Beijing-based Grandview Institution published an assessment of the US satellite images, saying that, as of November last year, Vietnam had added “3 sq km (1.2 sq miles) of new land, far exceeding the total construction scale over the previous 40 years”.

In June, the US think tank said Vietnam was “on pace for a record year of island building in 2024”, calculating that its land holdings covered seven times the area they did three years ago.

Beijing is certainly concerned by Hanoi’s actions – which mirror its own decade-long drive to build artificial reefs and facilities in the areas it controls – and it has periodically issued threats to its Vietnamese partners, according to Isaac Kardon, a senior fellow for China studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

However, their growing closeness on security matters has “downgraded the issue in their bilateral diplomacy”.

“China is pursuing a different type of bilateral relationship with its southern neighbour characterised by increasingly close [Communist] party-to-party ties and mutual commitment to keep their maritime disputes from displacing their wider cooperation,” Kardon added.

Last month, during the visit to China by Vietnam’s new leader To Lam, the two sides agreed to try to solve the dispute through “friendly consultations” and said there was a “high-level” consensus on the need to maintain peace and stability in the region.

Van Pham, founder of the South China Sea Chronicle Initiative, a Vietnam-based think tank, said Beijing wanted to work with Vietnam on infrastructure projects, including railways, and wanted its support for projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative.

“These economic connections serve as a buffer against outright hostility, encouraging China to adopt more restrained tactics,” Pham said.

Ray Powell, a maritime specialist at Stanford University, said Hanoi had taken advantage of China’s focus on the dispute with the Philippines to accelerate its island-building campaign.

“Hanoi has, in choosing this moment, opportunistically stolen a march on Beijing in the South China Sea,” Powell said, adding that China might have paid more attention to Vietnam’s activities if the Philippines had been more “compliant”.

Instead, the Philippines has also been quick to highlight clashes by releasing video footage of collisions and China’s use of water cannons, as well as giving maximum publicity to incidents such as a clash in which Philippine sailors, one of whom lost a thumb, were allegedly attacked by coastguard personnel armed with knives and machetes.

These incidents have led to public condemnation of China’s actions from a variety of foreign governments and forced Beijing to defend its stance and try to avoid reputational damage.

Analysts also said the long-standing US-Philippine alliance and President Ferdinand Macros Jnr’s efforts to strengthen the relationship with Washington were another factor in Beijing’s thinking.

Last year the two allies revived a defensive pact that granted the US access to four additional bases close to strategic hotspots such as Taiwan and the South China Sea.

The Philippines has also stepped up joint exercises, both with the US and countries such as Japan, Canada and Australia.

According to an associate professor in Guangzhou, who specialises in the South China Sea and asked to remain anonymous, Manila’s closeness to the US, the “collective effort to intimidate China” and its willingness to support Washington’s stance on Taiwan was “intolerable” to Beijing.

Beijing views Taiwan as part of its territory that must be reunited with the mainland, by force if necessary.

Most countries, including the US and Philippines, do not recognise Taiwan as an independent state, but Washington opposes any attempt to take the island by force and is legally bound to arm the island to help it defend itself.

The academic said Beijing now felt forced to leverage the South China Sea dispute to put pressure on Manila.

“Unlike other nations that engage frequently in joint military exercises with forces outside the region, Vietnam has been notably restrained in colluding with extra-regional powers,” the associate professor added.

Zack Cooper, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, said Beijing may want to discourage other South China Sea claimants from following the Philippine lead.

“[China] feels that pushing back hard against the Marcos government is useful to teach other countries a lesson about aligning too closely with the US,” he said.

Harrison Prétat, a maritime affairs expert at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, said: “It is likely that some amount of the pressure Beijing has applied to Manila’s maritime activities has been an attempt to test US-Philippine unity and raise doubts in the Philippines about the usefulness of the alliance.”

But he also said that it may be worried that taking a tough approach to the Philippines and Vietnam at the same time could “strain its resources and amount to an untenable level of risk”.

Pham, from the South China Sea Chronicle Initiative, said: “Missteps in exerting pressure on Vietnam will only drive Vietnam closer to the US and other regional powers, complicating China’s strategic calculations in the South China Sea.”

Prétat also said Vietnam “prefers to manage maritime tensions with Beijing quietly and is unlikely to follow in Manila’s footsteps”, adding that the Philippines has tried to “internationalise” the dispute.

In 2016 it took a case to an international tribunal in The Hague, which rejected Beijing’s claims over the waterway, and it is now considering another lawsuit alleging that China has caused environmental damage in the waterway.

China refused to take part in the 2016 hearings and has never accepted the findings.

Ding Duo, from the National Institute for South China Sea Studies in Hainan, said Manila tended to “escalate the issue as much as possible” but “high-level officials and leaders in Vietnam rarely talk about the dispute internationally or point their fingers at China”.

But Zhu Feng, executive dean of Nanjing University’s school of international studies, said the “potential threats posed by Vietnam’s island-building have not been completely eliminated”.

Zhu added: “Such activities could become a new flashpoint in the bilateral relationship if there is a substantial change or escalation.”

According to Ding, Beijing’s different approach towards the two countries stemmed from the fact that Vietnam was building “on features it has controlled since the 1970s and 1980s, while Beijing views Manila’s efforts as an attempt to take over previously uninhabited features or those under Chinese control, such as Scarborough Shoal”.

Ding said Beijing may think Manila’s actions were “unacceptable” and not in line with the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea.

This non-binding guideline signed by China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 2002 says countries should not establish a presence on uninhabited islands or reefs and should exercise self-restraint.

In 2013 China embarked on a major island-building programme of its own in the Spratly Islands, and also built up both civilian and military infrastructure in the South China Sea, including runways, radar stations and accommodation for troops.

All this construction happened on features that Beijing already controlled and state media has defended its actions as “lawful and justified”.

Pham said the key to China’s approach was “divide and rule tactics” because it wanted to forestall any collective resistance among claimant states to maintain its dominance in the South China Sea.

However, Cooper warned, tough measures from Beijing could not be ruled out in the future, “if more substantial military forces start being deployed more regularly to those [Vietnamese] features”.

ng launching another lawsuit that targets the environmental damage by China.

For the latest news from the South China Morning Post download our mobile app. Copyright 2024.