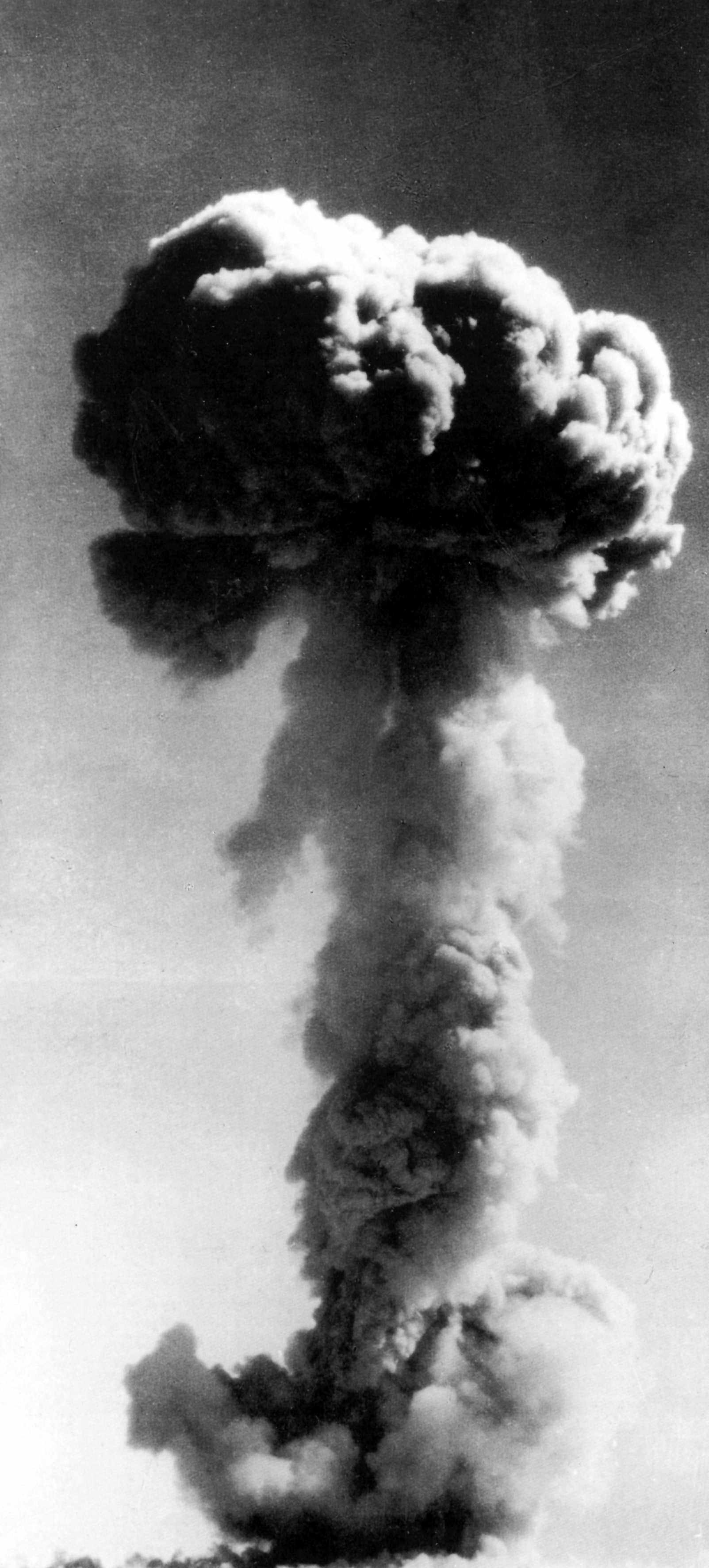

Sixty years ago, in the remote Lop Nur desert in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, China successfully detonated its first atomic bomb, code-named “Miss Qiu”.

The test, on October 16, 1964, and the fission chain reaction it triggered, melted the top half of a 120-metre (394 feet) high iron tower. It was a pivotal moment in China’s pursuit of nuclear weapons.

The experiment was conducted at a time of immense political challenges: the nation’s alliance with the Soviet Union had fallen apart and Moscow had withdrawn its technological help in the late 1950s, China was mired in a deep economic crisis.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

But the detonation put China on a fast track to grow its nuclear strength before an important deadline that had been drafted by the United States, the former Soviet Union and Britain for the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons Treaty (NPT).

The deal determined that the beginning of 1967 would be the cut-off date to identify and recognise countries with nuclear weapons as rightful “nuclear-weapon states” that had the privilege to possess the mass destructive weapon lawfully.

At the same time, while China was developing its nuclear weapons programme, it was also developing its missile technologies. On October 27, 1966, China launched a Dong Feng-2 (DF-2) medium-range ballistic missile with a nuclear warhead mounted on it. The test gave China the capability of delivering a nuclear bomb by missile instead of by aircraft.

On June 17 the following year at Lop Nur, China tested its first thermonuclear device – a hydrogen bomb – a more advanced type of nuclear weapon.

As the rivalry between China and the US has grown, Washington has become wary of Beijing’s deterrence strategy by expanding its nuclear capabilities and arsenal of advanced weapons.

A paper tiger we cannot do without

On Aug 6, 1946, one year after the Hiroshima bombing, Mao Zedong was interviewed by American journalist Anna Louise Strong.

“The atomic bomb is a paper tiger used by the American reactionaries to scare people,” said Mao, who described the new killer weapon as scary looking, but in fact toothless.

“Of course, the atomic bomb is a weapon of mass slaughter, but it is the people, not one or two new weapons, that decide the outcome of a war,” he explained.

Historian Zhang Jing of Peking University has suggested that the “tactical” gestures of defiance were intended to boost the Communist Party’s morale as civil war loomed in China, heightening fears the US may intervene and use atomic weapons.

Ten years later, Mao announced during a speech that China would pursue advanced defence technologies, including nuclear weapons.

“Not only do we need more aircraft and artillery, but also the atomic bomb. In today’s world, we cannot do without this thing if we do not want to be bullied by others,” he told a Politburo meeting in 1956.

The decision was motivated in part by the technological shortcomings of the Chinese military during the Korean war, the First Taiwan Strait Crisis that began in 1954, and the build up to the Vietnam war. But according to Zhang, Moscow’s pledges to help Beijing develop nuclear technologies also played a role.

With national strategy and policy set, recruitment of nuclear physicists like Deng Jiaxian and other scientists was soon under way. Research institutions were established and facilities were built, including the country’s first heavy water reactor and cyclotron. Uranium mines in the provinces of Jiangxi and Hunan also went into operation.

But within a few years, relations between Beijing and Moscow had soured and the Soviets halted aid and pulled their nuclear experts out of China, destroying all related documents as they left. It was June 1959, and suddenly the Chinese had to carry on by themselves. They named their independent atomic bomb programme “Project 596” to mark the bitter split.

Within the party’s leadership there were fierce debates about the bomb, with some suggesting the weapons project be put on hold as the country suffered through famine. But military chiefs at the time, such as Lin Biao, vice-chairman of the party, and Marshal Nie Rongzhen, vice-premier and head of the Commission of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defence, insisted the programme must continue, according to the memoir of General Li Xuge, former commander of the People’s Liberation Army’s Second Artillery Force.

One of the strongest proponents was foreign minister Chen Yi, who famously said “we must get the atomic bomb even if we have to sell our pants”. In July 1960, the debates had been laid to rest with Mao telling everyone to “be determined to work on cutting-edge technologies”.

By August 1964, construction of the U-235 fuelled implosion bomb had been completed and Chinese intelligence reports suggested the Americans or even the Russians might have been considering taking action against China’s nuclear facilities. That was confirmed decades later in declassified US documents.

In response, Mao reiterated that the purpose of the atomic bomb was “to scare others, not necessarily to be used in practice”.

“Since it is for intimidation, better have it go off earlier,” he ordered on September 20. The world heard the blast less than a month later.

In January 1965, two months after China became the fifth country with nuclear weapons, Mao was asked by journalist Edgar Snow about the “paper tiger” theory again.

“A nuclear bomb kills. But in the end, it will be annihilated eventually. In this sense, a nuclear bomb is really a paper tiger,” Mao replied.

“No first use” from day 1

Hours after the device was detonated on October 16, 1964, the Chinese government immediately declared the “no first use” nuclear weapons policy, that it “will never, at any time or under any circumstances, be the first to use nuclear weapons”.

Beijing later added that it pledged “unconditionally not to use, or threaten to use, nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear-weapon-free zones”, and started urging the four other nuclear powers of the time to commit to “no first use”.

Sixty years later, Sun Xiaobo, the foreign ministry’s director of the department of arms control told a UN meeting that “China has always and will continue to maintain its nuclear forces at the lowest level necessary for its national security.”

The statement was in line with the theory that opposition from people across the world would make the use of nuclear weapons taboo, according to Professor Li Bin, an international relations and nuclear arms control expert at Tsinghua University.

“Because of this nuclear taboo, nuclear-weapon states cannot initiate nuclear weapons in a conventional conflict,” he said, adding that the events of the past decades have proven that even if nuclear-weapon states struggle in a conventional conflict, they dare not use nuclear weapons to save the day.

Li said China’s “no first use” commitment is based on the assumption that no one can really be the first to use nuclear weapons in a conventional conflict.

Under that premise, Chinese leaders from Mao onwards have tended to stress the political significance of nuclear weapons, rather than regarding them as an actual military weapon to be deployed in a war, Zhang said.

“In the view of the Chinese leaders, the development of nuclear weapons could lead to the development of modern science and technology ... and help China regain status in the international community, on top of national security concerns,” she said.

Despite the challenges, Chinese researchers carried on: the first ICBM DF-5 full flight test was conducted in May 1980; the last atmospheric nuclear test was carried out that October; the submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) JL-1 was tested in 1982; and in 1983, the Type 092 SSBN – China’s first and only nuclear powered ballistic missile submarine that was capable of firing an SLBM by then – was commissioned.

Then, in 1985, Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, downsized the People’s Liberation Army by one million personnel, in a major pivot towards economic development.

“One of the important reasons why China’s reform and opening up policy was successful was the security guarantee and confidence the nuclear capabilities brought to China as a responsible major power,” Zhang said.

Is “minimum deterrence” still valid?

As the massive lay-offs were under way, Deng told the PLA to “be patient for some years”.

“I see by the end of this century we will certainly have exceeded the goal of quadrupling [the GDP], and by that time we will be financially stronger and will be able to spend a relatively large amount of money to update our military equipment,” he promised.

During the “patient years”, many major defence programmes were scrapped or suspended. But by the time China had joined the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1996, the nation had conducted a total of 45 physical nuclear tests.

Based on those experiments, Chinese scientists had finished building a neutron weapon in 1988, confirmed possession of a miniaturised hydrogen bomb in 1999, constructed solid-fuel nuclear-capable ballistic missiles – the DF-21 and DF-31 – as well as the SLBM JL-2, and had finally fielded sea-based nuclear capabilities with the JL-1A on the Type 092 submarine.

By 1999, as Deng had predicted, China’s economy was booming, and the military budget began to soar over. Most of the money has been spent on conventional capabilities. China maintains a “minimum nuclear policy”, but its nuclear arsenal has been boosted significantly thanks to the introduction of new SSBN Type 094, the new SLBM JL-3, the DF-5C, road-mobile ICBMs DF-31AG and DF-41, nuclear-capable IRBMs DF-21D/26 and the hypersonic glider DF-17, as well as a nuclear-capable strategic bomber modified from the older platform H-6 series.

Over the past several years, as the risk of military confrontation with the West has grown, many believe China has shifted away from its “minimum deterrence” strategy, despite President Xi Jinping’s insistence that “nuclear weapons must not be used, and nuclear wars should not be fought”.

According to a Pentagon estimate last year, Beijing possessed more than 500 operational nuclear warheads as of May 2023, would probably have more than 1,000 operational nuclear warheads by 2030, and would continue growing that number until 2035, resulting in a nuclear arsenal comparable to the US and Russia.

“Compared to the PLA’s nuclear modernisation efforts a decade ago, current efforts dwarf previous attempts in both scale and complexity,” the 2023 China Military Power Report said.

Construction of at least 300 new ICBM silos in northwestern China was probably completed in 2022, with some of them armed. Alongside new fast breeder reactors and reprocessing facilities, China has been expanding its number of land, sea and air-based nuclear delivery platforms, while investing in and constructing the infrastructure necessary to support further expansion of its nuclear forces, including DF-5C and JL-3 missiles, according the report.

More from South China Morning Post:

- What is the DF-41 missile and how does it fit into China’s ICBM programme?

- Why China’s ‘no first use’ policy requires more nuclear weapons

- What do Taiwan Strait sightings of Type 094s say about China’s nuclear sub force?

For the latest news from the South China Morning Post download our mobile app. Copyright 2024.