The US presidential race between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris comes at a time of rising geopolitical tensions on multiple fronts. In the fourth of a series, Bochen Han reports on how legislation targeting Chinese citizens has mobilised voters in Texas.

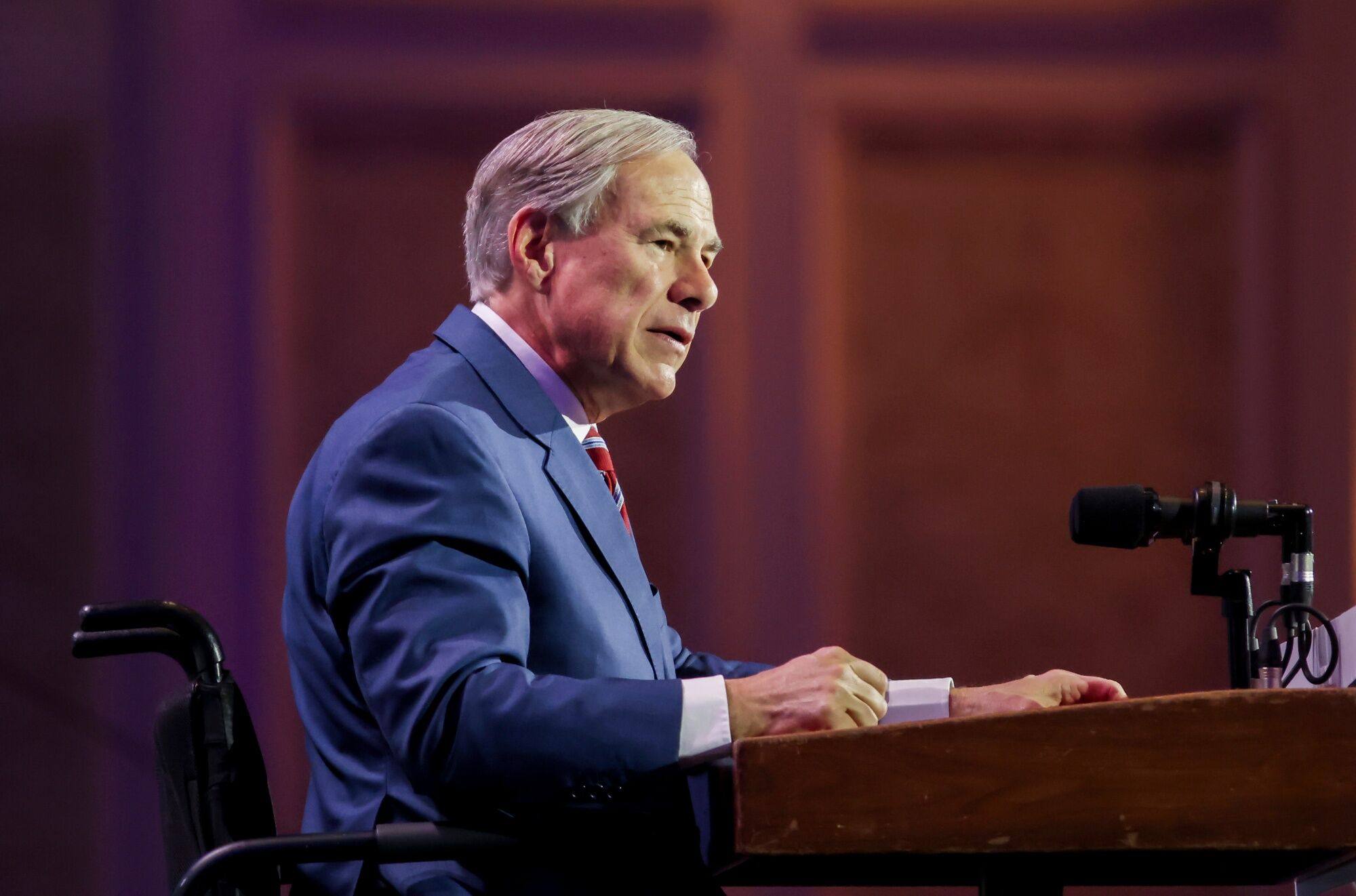

For Lan Wang, life in Texas was good until she heard in early 2023 that Governor Greg Abbott would support a bill that would prevent Chinese citizens from buying property in the state.

“My initial thought was, this was a joke,” she said.

Angered, Wang – a Dallas resident who asked to use a pseudonym – began learning about the state’s legislative process and attending hearings related to the bill.

Even though she had studied public policy, and felt uncomfortable when anti-China rhetoric was being spread during the Covid-19 pandemic, she said it was only last year that she felt motivated to take action.

Early versions of Texas Senate Bill 147 – one of numerous Republican-sponsored measures introduced nationwide in recent years aimed at restricting property purchases by citizens of “adversarial” countries like China – would have imposed restrictions even on Chinese green card holders.

At the time, the restrictions would have directly affected Wang, who arrived in Texas as a student in 2010 and became a US citizen only late last year.

Although the bill was later watered down and ultimately died, Wang has remained politically engaged, joining the ranks of many Chinese-Americans in Texas who became politically involved because of the legislation.

Ahead of the November 5 election, Wang says she plans to help with efforts to increase voter turnout.

“The anti-alien land law issue in Texas has ignited a lot of debate and led to a lot of Asian-Americans participating in politics and in government in a way that I’ve certainly never seen before,” said Lily Trieu, executive director of Asian Texans for Justice, a non-profit group based in Austin.

Trieu, whose organisation provides advocacy training, described seeing “unprecedented” numbers of Chinese-Americans not only displaying political awareness, but also donating money, hosting rallies and actively participating in the legislative process.

“The Chinese community in Texas is feeling attacked by its own government in a more visceral way than they have felt in years,” she said.

According to some Texas legislators, property ownership by “hostile” foreign countries like China, Iran, North Korea and Russia poses risks of espionage and economic influence.

Critics, citing historical examples of exclusionary legislation against Chinese people, argue that restricting ownership by specific countries will unfairly stigmatise people from those nations, even if the bill does not target individuals.

In July, the Committee of 100, a non-partisan Chinese-American civic group, reported that 151 bills restricting property ownership by foreign entities have been considered in 2024 at the state and national levels, with 71 specifically targeting Chinese citizens.

Efforts to oppose the Texas bill were more successful than in other states, like Florida, where similar restrictions became law.

Trieu partly attributes this to the state’s sizeable Asian-American population, which exceeds 1.5 million, as well as the population’s concentration in urban areas, which she said made mobilisation easier.

Chen Liang, a researcher at the University of Texas at Austin, suggests that the relatively long presence of Asian-American groups in Texas may have provided an advantage compared with other Southern states.

But despite the backlash to SB 147, Texas state lawmakers are threatening to bring a version of it back, in addition to other legislation that targets Chinese influence. In July, Republican State Senator Lois Kolkhorst vowed to introduce an anti-foreign land ownership bill in the next legislative session, which begins in January.

Last month, a group of Chinese-Americans gathered in Tyler, Texas, to protest the bill’s revival at a hearing of the Select Committee on Securing Texas from Hostile Foreign Organisations, a committee in the state’s House of Representatives.

Texas consistently votes Republican at both the state and national levels, with districts in the major cities typically held by Democrats.

The state is also home to one of the fastest-growing Asian-American populations in the country – a group that has been critical in turning previously Republican-dominated states like Georgia competitive in recent national elections.

These voters could prove crucial this year in Texas, where a tight US Senate race has emerged between Republican incumbent Ted Cruz and US Representative Colin Allred as Democrats try to retain control of the chamber in November.

According to Hugh Li, president of the Austin Chinese-American Network, SB 147 united Chinese across the political spectrum, and has led to greater coordination between advocacy groups in major Texas cities, including ones representing other nationalities targeted by the bill.

That coordination, Li says, effectively sets Chinese-Americans up to resist other “extreme” bills that he foresees coming due to the tense nature of the US-China relationship.

Li stresses, however, that it is not yet clear that frustration about anti-Chinese legislation would push a critical mass of Chinese-Americans to vote for a particular party across both state and national levels in Texas.

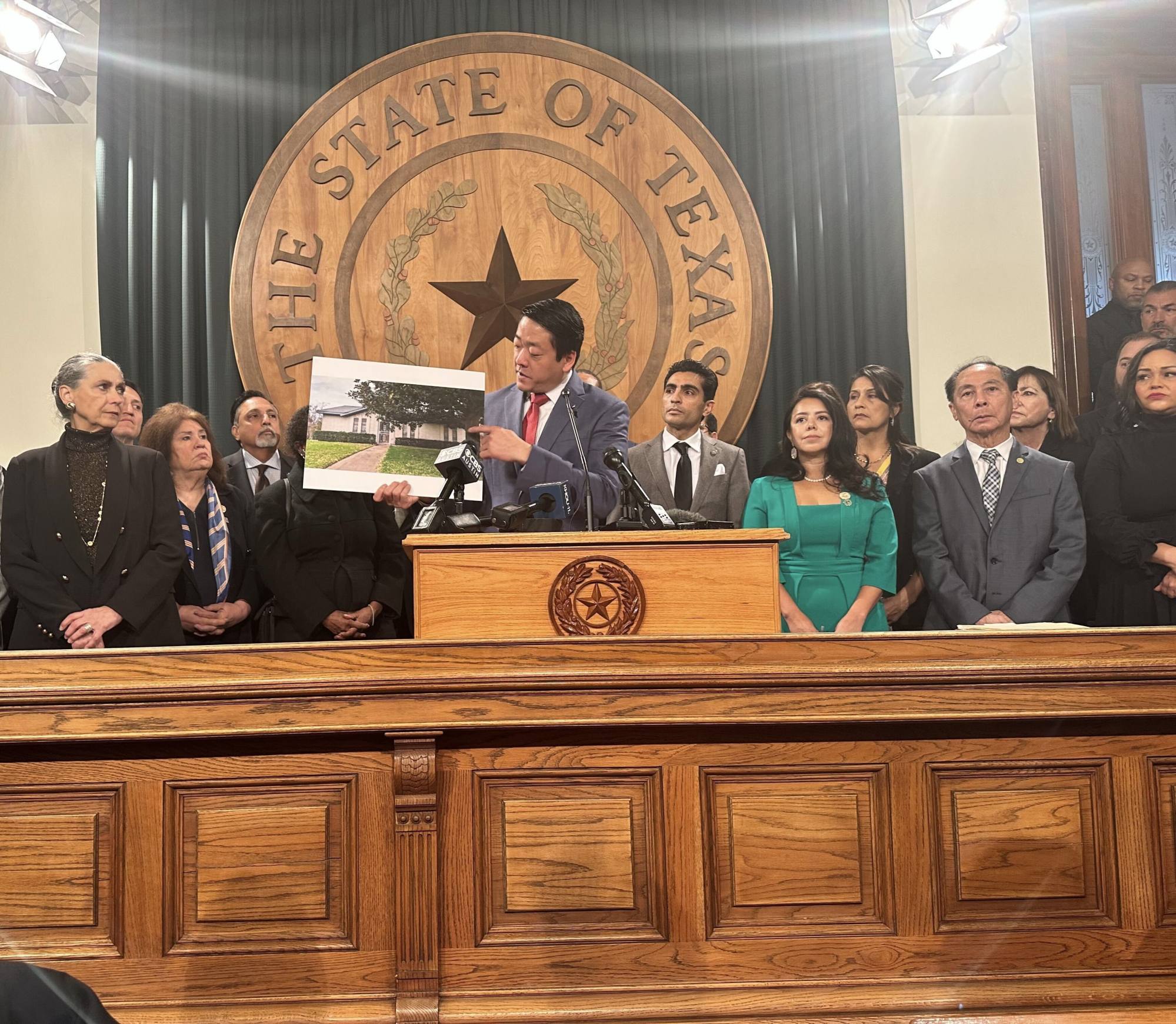

For Gene Wu, a Democratic representative in the Texas House, the battle extends far beyond state politics. Citing proposed land bans and visa restrictions for Chinese nationals in Project 2025, a blueprint by the conservative Heritage Foundation think tank for a second Donald Trump administration, Wu called the fight “existential” for Chinese-Americans.

“It doesn’t matter who you are, it doesn’t matter that you’re a citizen ... everybody is a spy, and that’s what we’re fighting against,” he said.

Over the past few months, Wu has travelled across the country sharing lessons from Texas’ recent experience with other states.

According to a 2024 survey conducted by AAPI Data, a research centre based at the University of California, Berkeley, Chinese-Americans lean Democratic but have the largest proportion of independent voters – 35 per cent – compared with other Asian-American subgroups. The survey sampled 2,479 Asian-Americans, of which 432 were Chinese.

National data on Chinese-American political engagement paints a picture of relatively low civic engagement.

Among Asian-American subgroups surveyed by AAPI Data, Chinese-Americans are the least likely to discuss politics on social media, contact a local representative or attend a protest. Still, 88 per cent of them say they plan to vote in November.

For some Chinese-Americans in Texas, the targeting of Chinese property ownership led them to realise the importance of showing the richness of Chinese culture to other Americans.

Yeung, a Houston-based artist who wanted only her last name used for fear of political reprisal, said the anger and alarm she experienced as a result of SB 147 drove her to seek community help to start a cultural organisation “to tell politicians to stop demonising the Chinese community”.

“I do not want my kids living in a hostile environment so I thought, I need to get up and fight,” she said, adding that she plans to make political statements through her art.

Yeung, who immigrated to the US from China when she was 16, said that despite living in Texas since 2000, she had never experienced as much hostility as she has in recent years.

“I never thought of myself as a liberal,” she said, but noted that she won’t vote for the Republican Party this election cycle, partly because of its leadership on anti-Chinese property ownership legislation.

In Florida, too, activists note that legislation against property ownership by Chinese citizens has ignited some unprecedented mobilisation among local Chinese-Americans.

The Orlando-based Florida Asian-American Justice Alliance (FAAJA), for instance, was formed in the wake of SB 264, a Republican-sponsored bill targeting citizens of China and six other countries that became law in May 2023.

On September 29, 2024, FAAJA Central Florida distributed voter registration postcards at major Asian grocery stores in Orlando to encourage the community to register before 10/7 deadline and stay informed about the key election dates. Every vote counts! pic.twitter.com/9NtCScPLE1

— FAAJA (@FAAJAFlorida) October 5, 2024

The FAAJA is one of several groups supporting a suit against the law in court.

Eagerness to participate politically as a result of targeted rhetoric and policies appears to be nationwide.

A 2024 report based on a survey of 1,005 Asian-American adults by Stop AAPI Hate, a San Francisco-based non-profit, showed that 85 per cent of respondents were concerned about the general US racial climate.

The report also found that 70 per cent were motivated to get involved in efforts to advance justice and equity for Asian-Americans, and that the “most concerned and activated” respondents were those who personally experienced an incident of hate.

But while it is unclear whether the concern will translate into electoral outcomes, Trieu of Asian Texans for Justice said the level of involvement by Chinese groups who have historically not been involved in politics was notable in a conservative state like Texas.

“To see it happen in Texas, a red state, a state in the South, to see it happen the way it did in 2023 and how it continues to go on now, this is something that I haven’t seen in my lifetime.”

More from South China Morning Post:

- Citing security risks, US states move to bar Chinese land purchases and projects with China ties

- Chinese-Americans in Texas protest ‘hateful’ state senate bills

- Florida’s Ron DeSantis signs bills limiting Chinese land ownership, TikTok at schools

For the latest news from the South China Morning Post download our mobile app. Copyright 2024.