As Europe scrambles to rearm its militaries, Brussels has trained its crosshairs on a long-standing trade problem that it now fears could present a new security challenge: China’s excess steel capacity.

Cheap imports from “notably China and in recent years India” have placed Europe’s producers of steel in peril, the European Commission said on Wednesday.

Such competition brings the threat of deindustrialisation in that sector – mirroring an existing trend for aluminium, which would hamper the continent’s efforts to ramp up its military industrial base “with the flexibility and speed required in a fast-changing geopolitical context”.

Do you have questions about the biggest topics and trends from around the world? Get the answers with SCMP Knowledge, our new platform of curated content with explainers, FAQs, analyses and infographics brought to you by our award-winning team.

The commission now wants to put up several barriers to metals imports, measures meant to build an emphasis on security into the bloc’s economic policies.

The EU has long railed against China’s steel output, which represents more than half of the world’s total, but has been stirred into action by two factors emanating from the United States.

With US President Donald Trump’s sidelining of Brussels in his bid to bring a quick end to the war in Ukraine and apparent desire to deal directly with Russian President Vladimir Putin, America’s security blanket for Europe is no longer guaranteed, ushering in a new era of defence spending.

Furthermore, the US leader’s 25 per cent tariffs on global steel and aluminium from around the world has stoked fears that more shipments from China, and from other producers like Canada and South Korea, will flood European markets.

“The industry remains threatened by global excess capacities and by global distortions from China and other countries that artificially support their domestic industries or circumvent EU trade defence measures and sanctions,” the plan said.

In a “Steel and Metals Action Plan” unveiled on Wednesday, the plan proposed tightening steel import quotas by April 1, to reduce imports by a further 15 per cent. This would be an extension of a safeguard measure in place since 2018, which is set to expire in just over a year, a measure it also wants to expand in light of recent events.

“It is unreasonable to assume that the structural global overcapacities and their negative trade-related impact on the EU’s steel industry, which triggered the use of the safeguard, will disappear on 1 July 2026,” the plan read.

“On the contrary, the negative trade-related effects are likely to be exacerbated, as an increasing number of third countries are adopting measures aimed at limiting imports into their markets, resulting in the EU market becoming the main receiving ground of global excess capacities,” it explained, name-checking Trump’s metals tariffs.

Further to this, in a move aimed at halting efforts to divert steel shipments subject to quotas and tariffs via third countries to avoid those penalties, Brussels will assess whether the bloc needs a “melted and poured rule”.

This would allow it “to act against the country where the metal was originally melted, regardless of the place of subsequent transformation and the origin of the good as determined by the traditional non-preferential rules of origin”.

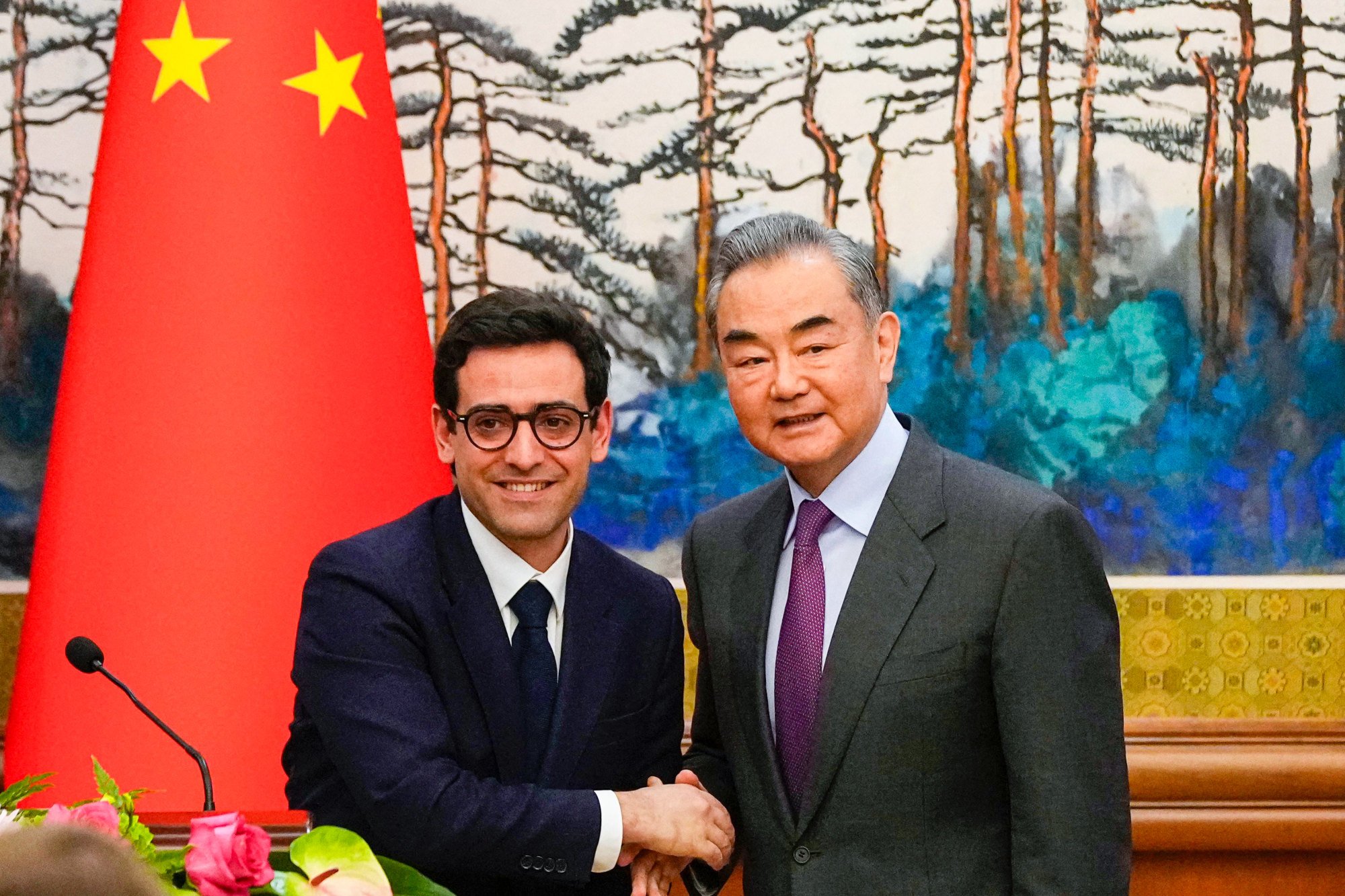

“Our competitors must not be able to take advantage of gaps in our regulatory framework, and this is why we are planning to make some changes,” said Stephane Sejourne, the European Commission’s executive vice-president.

For years, the EU has been complaining about the disparity between output and consumption in China’s steel industry.

European Steel Association data show China produces 55 per cent of global crude steel output. The new plan estimated that in 2024, global steel overcapacity was “more than four and a half times the EU’s yearly consumption”.

According to the OECD, “China’s steel trade surplus has surged to nearly 100 million metric tonnes in 2024, on an annualised basis, a massive leap that is affecting competition across global steel markets”.

Since the safeguard measures were introduced, however, China went from being the top supplier of steel to Europe in 2017 to fifth on the list, behind South Korea, India, Taiwan and Turkey.

Despite this, Chinese steel products are the most common targeted by EU regulators, which has seven ongoing trade investigations into Chinese steel products, as well as existing import restrictions and tariffs in place.

The commission now wants to start opening probes preemptively, looking for the threat of injury, rather than substantial economic harm.

“To address the fast developments in global markets and to protect the industry, the Commission will strengthen the monitoring of trade flows and will proactively open investigations based on a ‘threat of injury’, without waiting for material injury to occur,” the plan said.

More from South China Morning Post:

- Europe’s Trump dilemma: must it de-risk from both the US and China at once?

- European Parliament removes curbs on lawmaker meetings with China

- Trump threatens tariffs on European wine and spirits in escalating trade war

For the latest news from the South China Morning Post download our mobile app. Copyright 2025.