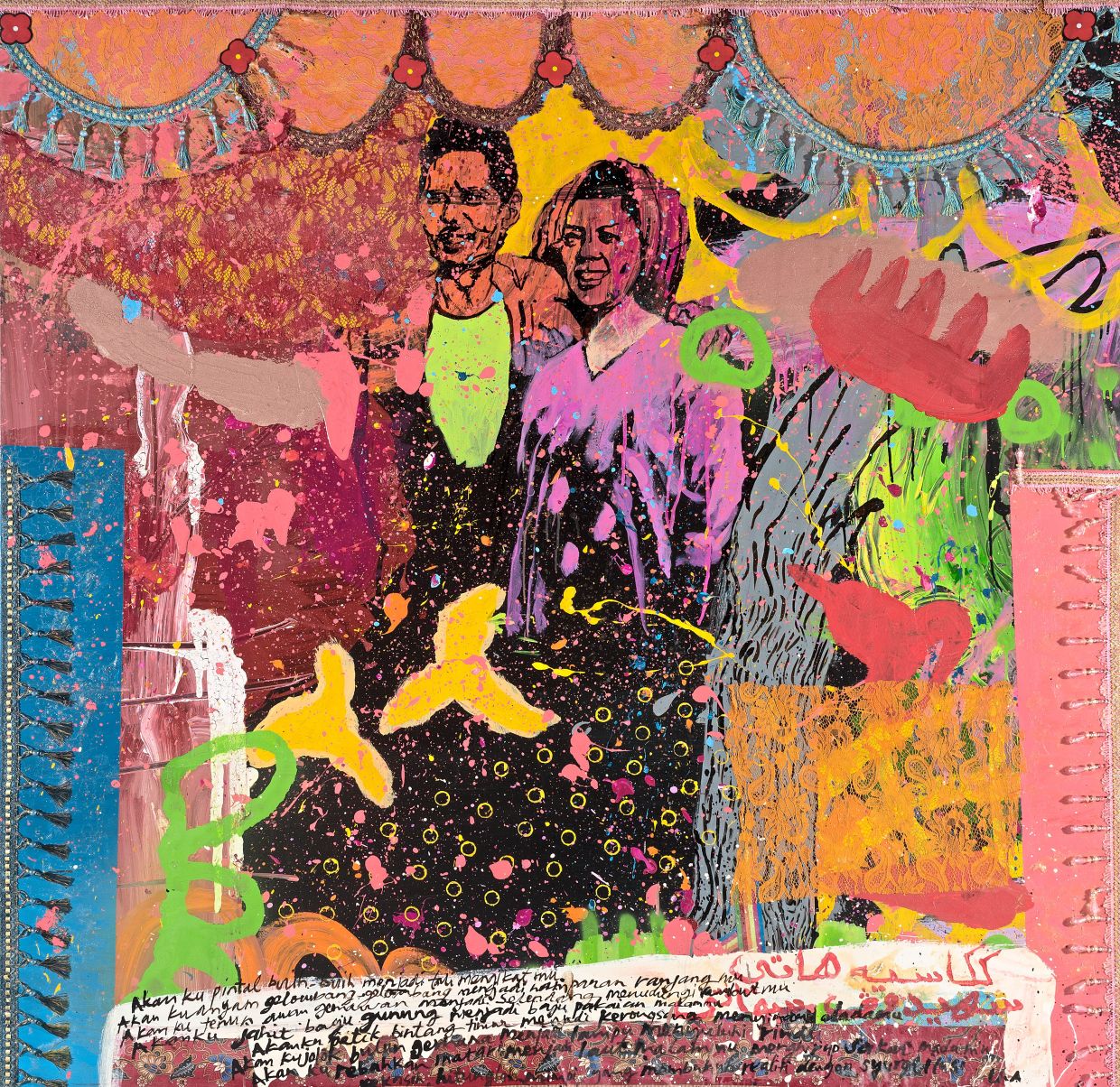

Jalaini pays tribute to classic Malay cinema in 'Kekasih Hati' (acrylic, bitumen, beads and fabric collage on canvas, 2023), which features actors Latifah Omar and Nordin Ahmad. Photo: Galeri Puteh

What comes to your mind when you see or hear the phrase “Malay kitsch”?

For contemporary artist and educator Jalaini Abu Hassan, or known to most as simply Jai, it conjures up images of traditional Malay weddings and the home he grew up in, decorated by his mother in the style that was typical for that time – lacy curtains, plastic flower arrangements and bucolic landscape artworks that you could find in many a Malaysian household.

Leaning forward in his seat, as though to tell this writer a secret, Jalaini asks, “Did you know that those landscapes were originally 19th century Dutch colonial propaganda of Indonesian landscapes?”

Nope, not a clue.

The 60-year-old artist, who has had a busy year with art and writing, goes on to explain that this type of art, depicting the beauty of Indonesia’s natural landscapes, is known as “Mooi Indie” in Dutch, meaning “Beautiful Indies”.

“The idyllic views of mountains, padi fields and rivers remind Malaysians of our own rural scenes, which is probably why it is so popular here.

“In the early 1970s, I remember seeing these Mooi Indie pieces everywhere in my kampung, decorating the walls of homes and shophouses. It was these landscapes that motivated me to paint in my teenage years. It was only later that I learned about their origin,” says Jalaini.

So what led him down this rabbit hole in the first place?

“I wanted to explore the idea of kitsch, particularly Malay kitsch, but there’s no word for it in Bahasa Malaysia – I even checked with Dewan Bahasa,” he shares.

“Although there is no specific term for it, kitsch has been a part of Malay culture – I grew up with it. So for my 30th solo show, I decided to do it on Malay kitsch. I think I’m qualified enough,” he adds with a laugh.

The good, the bad and the kitsch

If you look up the meaning of the word “kitsch”, it’s defined as “art, objects or design considered to be in poor taste because of excessive garishness or sentimentality”.

“But who are we to say that kitsch is ‘bad art’? People like kitsch for a reason, so you can’t dismiss it as bad art. That’s what I wanted to look at in this exhibition – how kitsch is defined and measured, especially from the Malay perspective,” says Jalaini.

In his latest solo exhibition, Melekat: Malay Kitsch at Galeri Puteh in Kuala Lumpur, Jalaini carefully curates vintage-like collages of fabric, beads, acrylic and bitumen reminiscent of the ones he made as a young boy.

“I grew up in a small kampung (Batu Kurau) in Perak, so the only exposure I had to the world beyond my kampung was through the wrapping paper our groceries would get wrapped in. Every time my mum came home from the grocery store, I couldn’t wait to open up the wrapping paper – these were newspapers and magazines that came from Thailand, Indonesia, Myanmar. I would carefully cut out the photos and stick them on my walls. I think that’s where my visual journey first began,” he recalls fondly.

According to Jalaini, the idea of “low art” and “high art” comes from the Western world.

“There’s this so-called classification that was determined by the West that if you’re cultured, you like high art, and if you’re not cultured, you like low art, and that’s something that many people have come to accept without question.

“But to me, high art or low art – it’s all subjective. If a certain piece of art makes you feel happy, if it speaks to you, then that is all that matters,” says Jalaini.

In looking into the history of kitsch, Jalaini found that it began after the Industrial Revolution, and with it, the rise of urbanisation and the middle class.

“People began to buy art and enjoyed it on their own terms and according to their means. I like that democratisation of art,” he adds.

If you want to know more about Jalaini’s thoughts on art, check out Sidang Sepetang, a book he put together looking back on his visual history, which also includes a funny, yet insightful essay on kitsch by his friend, Afiendi Salleh.

The book is one of the latest published works from him, including his first book of poetry, Catan Sopan (released in December last year), and his contributions to Cosmic Connections Langkawi, which features art, science and photography.

Not having a style is a style

“I try to run away from the responsibility of having a set style,” says Jalaini.

“There may be those that say that if you don’t have a set style, then that makes you inconsistent or unsure of yourself, but I don’t believe in limiting myself.

“Today, I may want to paint a landscape, then tomorrow I may want to do a still life. Not having a style is a style in itself,” he points out.

Jalaini, who currently teaches painting to Universiti Teknologi Mara students and serves as an adjunct professor at Universiti Malaya’s Faculty of Visual Art, encourages his students to do the same.

“The job of an artist is to create. Don’t worry about labelling your work – others will do that for you. Your job is to keep exploring, to keep reinventing yourself. Otherwise, you will become stagnant,” he advises.

For Jalaini, what’s key in an artist’s work is the storytelling.

“The best storytelling comes from your own story, your history – where you come from, how you started, based on your own little world,” he explains.

Though some may consider him a political artist, Jalaini himself does not see himself as one.

“I don’t see myself as a political artist, but I do express my thoughts and opinions through my art. To remain relevant as an artist, one must be aware of what’s happening in the current context. You can then choose to reflect on it or respond to it on your own terms.”

So which among the 16 new works in the Melekat: Malay Kitsch show is his favourite?

“Probably the most unpopular one – Mandi Bunga,” he shares with a wry smile.

Melekat: Malay Kitsch is showing at Galeri Puteh, KL Eco City Mall until Dec 17. Free admission. More info here.