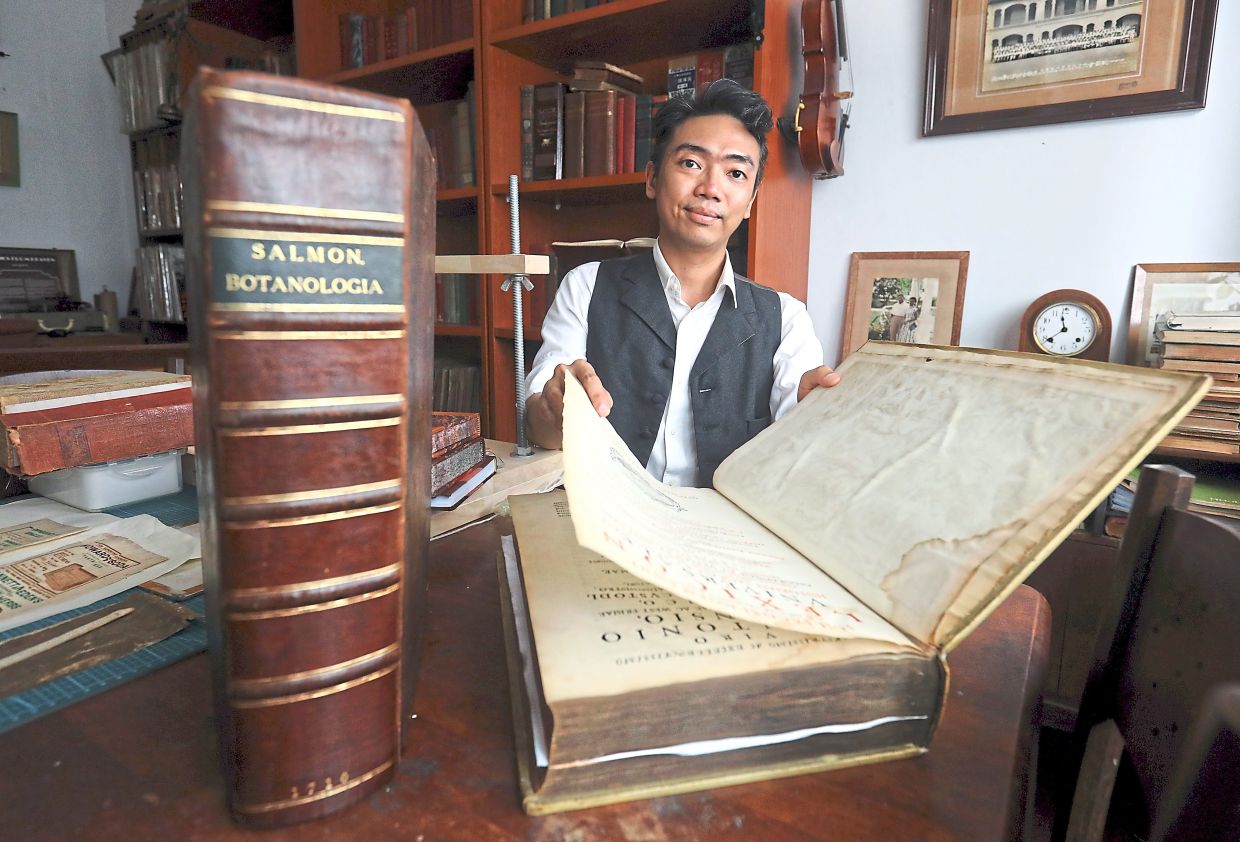

Luqman showing the process of 'threading' where pages are aligned in the sewing frame before being bound together. Photo: The Star/Azlina Abdullah

Luqman Azhar is a rare breed in the Malaysian old trades scene – a young man with a knack for breathing new life into antiquarian books.

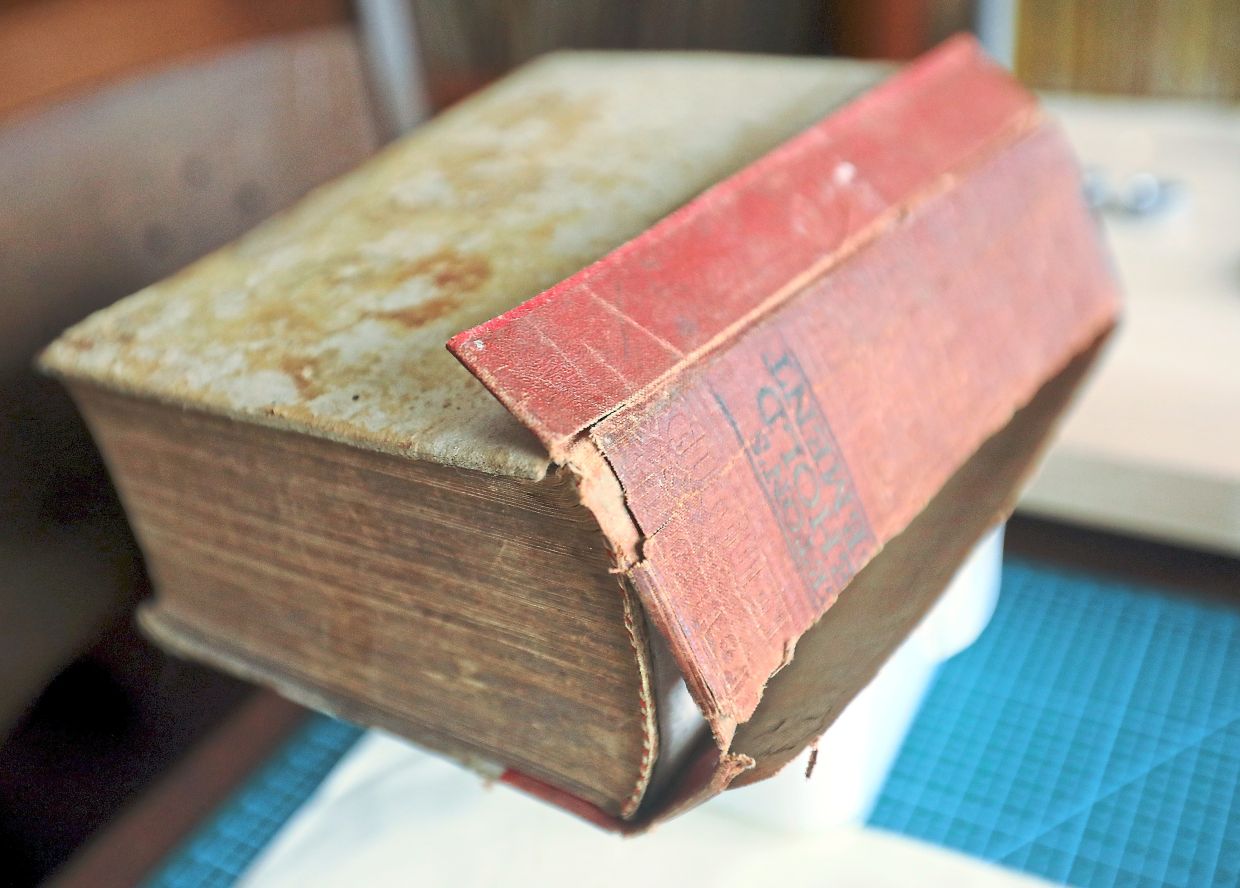

The 36-year-old avid reader and book collector turned his passion for antiquarian books into Shady Scrivener Co, a part-time bookbinding and restoration service he started in 2020. He also prints facsimiles of vintage books.

Uh-oh! Daily quota reached.