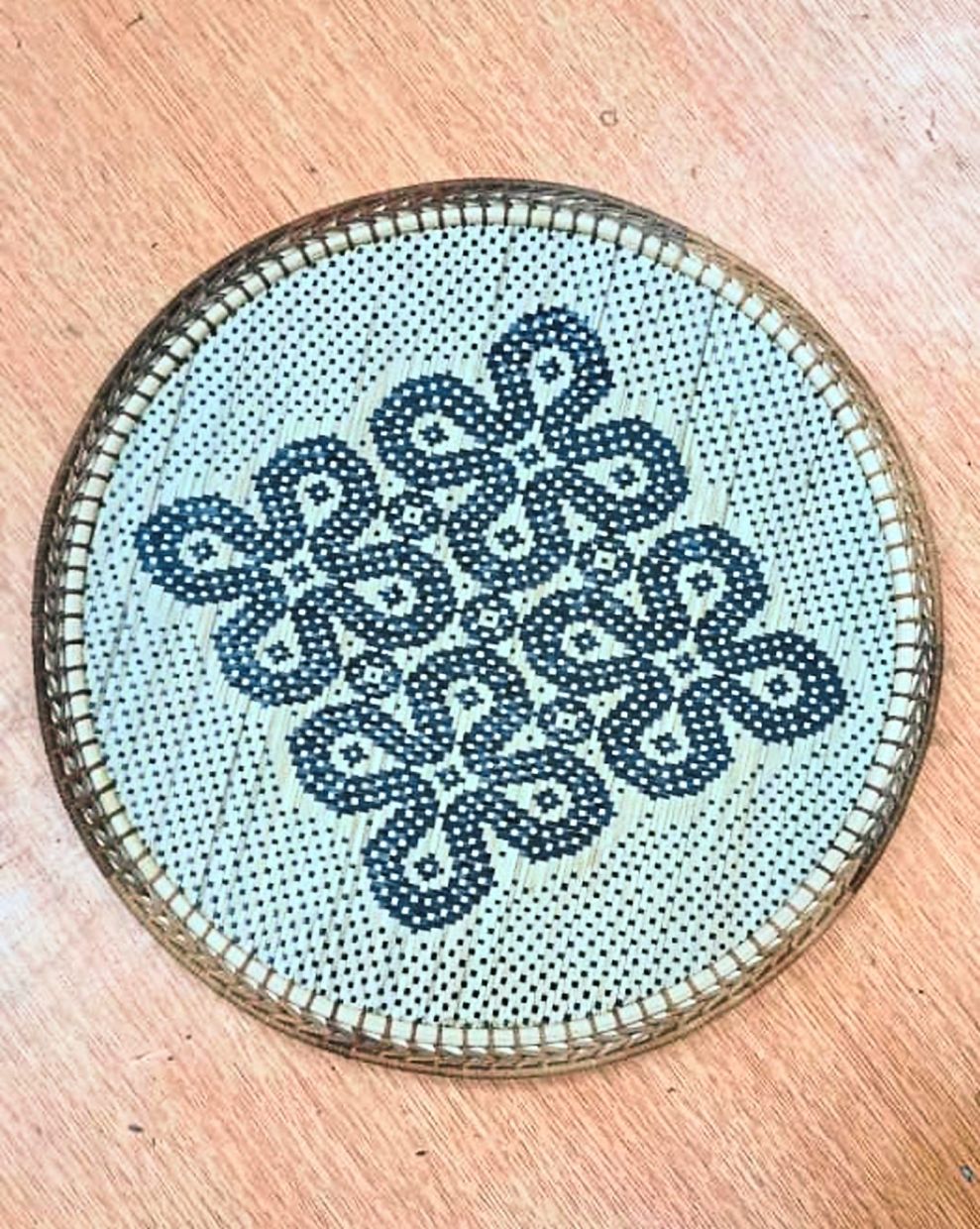

Roziah and one of her gorgeous creations at the exhibition in KL. — Photos: LOW LAY PHON/The Star

Weaving is one of the oldest surviving crafts, and it is a cultural heritage for many communities around the world. In Malaysia, different styles of weaving – cloth weaving, mat weaving and basket weaving, for example – can be found among various ethnic groups and communities.

For Sabahan weavers Roziah Jalalid, Julitah Kulinting and Lili Naming, weaving is an important part of their culture and tradition. Interestingly, though, all three women come from different ethnic backgrounds: Roziah is Bajau, Julitah is Dusun, while Lili is Dusun-Murut.

The trio were in Kuala Lumpur recently as part of the Borneo Heart In Kuala Lumpur art exhibition project, which was spearheaded by Sabahan artist Yee I-Lann. The exhibition also saw Yee launching her book, Yee I-Lann: The Sun Will Rise In The East, a 216-page monograph that traces the arc of the artist’s practice through a sequence of essays, conversations and photographs. Published by RogueArt 2023, the book is in English, with some text in Kadazandusun, Bajau and Bahasa Malaysia.

During the exhibition, too, a group of Sabahan weavers and dancers, as well as videographer/photographer Andy Chia, talked about their experiences of working in the project and having their work showcased internationally, in some sharing sessions.

Here are some of their stories.

ROZIAH JALALID

Roziah, 48, hails from Pulau Omadal in Semporna, Sabah. She has been creating traditional handwoven crafts for more than three decades, and says that weaving is part of her Bajau culture.

She is now trying to pass on her cultural heritage to her daughters, Tasya Tularan (13) and Dayang Tularan (12), who started learning the art a few years ago.

“Like any other form of artistic skill, you can’t force someone to pick up the craft if they have no interest in learning. But this wasn’t the case for my children. Even though they were very young, they were dedicated to learn how to weave, which really touched me,” said Roziah.

Roziah has a leading role in the Women’s Association of Pulau Omadal, which helps to improve the lives of the island’s community by creating artisanal products like mats and bags, and selling them in the big cities or to tourists. She is also part of the ISKUL Sama DiLaut, a school that was set up mainly for the stateless children on the island.

Roziah donates a portion of the sales of her own products to the World Wide Fund for Nature Malaysia, too, to help with conservation works on Pulau Omadal.

She has remarkable weaving skills, and has even won a few awards to prove it. She uses leaves found and harvested on the island, like pandan, to make her traditional mats, which come in various colours. She noted that one of the most commonly used natural dye is turmeric, which produces a yellow hue.

“Depending on the size of the art piece, the weaving process can take up to two months, or more. A 150cm x 250cm mat will need about two months to finish,” she said, adding that the designs and patterns of the mat are inspired by nature, and one’s surroundings.

“The various motifs symbolise our life, the things we see around us, and the environment we live in,” Roziah shared.

One of the more interesting designs is the “harunan motor”, which refers to the small steps outside of one’s house. As Pulau Omadal is a water village, the houses there are all built on stilts, and the villagers move around mostly by small boats or sampan.

There’s also the prawn and starfish motif, which represent marine life, and the “sambulayang” or Bajau flag, which Roziah said is a popular design.

The weaver said that she is happy that traditional Bajau weaving, as well as other forms of traditional weaving in the state, is in the spotlight again. Roziah thinks that the creative ways with which people are incorporating weaving into modern-day products may just help conserve the art for future generations.

“I’m happy that the craft is finally becoming popular and that more people are learning to appreciate the art,” she shared.

JULITAH KULINTING

For Julitah, 57, weaving was a way for her to survive. Growing up on a farm in a remote village near Keningau, Julitah said that almost everything in her home back in the day was handmade.

“I had never seen a car until many, many years later – that was how isolated my village was. I couldn’t go to school because it was too far and we didn’t have the money for it. When we needed something, we had to make it ourselves,” Julitah said.

She got married when she was still a teenager, and had her first child two years later. Marriage and motherhood helped improve her life a little bit, until her husband lost his job. Julitah realised then that she could actually put her weaving skills to good use, and make some money out of it.

“I needed diapers, milk, food. So I had to come up with a way to sustain our lives, and move forward. Eventually, weaving became my bread and butter,” she said.

Today, Julitah is enjoying her life as a “retiree”, as she no longer teaches the art of weaving to students. However, she did pass on her knowledge to her children – she has 10 of them!

She revealed that her three eldest daughters – Julia Ginasius, 41; Narty Raitom, 39 and Zaitun Raitom, 30 – are really skilful weavers, and talented too. Julia picked up the craft a little later than her siblings, as she prefers to sew and make contemporary bags and accessories.

Narty has 20 years of weaving experience, and is now a textile artist and designer who has her own label, making and selling handicraft bags.

She is currently preparing for her first solo exhibition.

Zaitun, meanwhile, started learning how to weave from her mother when she was 12. She aspires to share her mother’s weaving knowledge and stories with others, to continue the traditional art.

In contrast to the Bajau people who weave with pandan leaves, the Dusun people use bamboo and rattan. Julitah said bamboo was once a common plant found in the wild, but it is becoming more difficult to get your hands on some now due to continued deforestation. She said that the best way to “fix” the material shortage is to start replanting them.

Of the many weaving patterns, Julitah is most proud of the “nandus andus”, a popular motif among the Dusun Minokok group that’s heavily influenced by the spears carried by headhunters.

Another unique Dusun style is the “pinuru langsat”, which reflects strong familial bonds. As Julitah explained, the closely woven flowers in the design signify the inseparable and strong connection of a family.

There is also the “binangkait” pattern that draws its inspiration from ferns.

There are, in fact, many Dusun weaving patterns and motifs, and it is challenge to tell them apart. This makes people like Julitah invaluable in the preservation of this heritage.

LILI NAMING

Weaving is more than a source of income for Lili – it is also her source of happiness.

Lili, 49, started weaving when she was 12. While other children her age were playing in the field, Lili happily spent time at home, watching her mother work on a weaving project. Soon, she tried her hand at the craft too, and found that she had a knack for it.

“My parents relied solely on the produce we harvested from our small backyard farm as my father did not work anywhere else. So, my mother was especially happy whenever she got orders for her weaving products. Her weaving skills helped to improve my parents’ financial situation, and raised us.

“That was what sparked my interest, too – I was inspired by my mother’s dedication,” said Lili.

She joined a two-year course organised by Pusat Kraftangan Sabah when she was in her 30s, which allowed her to perfect her skills and push her even further creatively. The course also gave her the proper knowledge, as well as the platform, to sell her products.

Lili excelled in her work and did pretty well for herself that she was even asked to train newcomers at the centre.

Entwined in tradition

Roziah and one of her gorgeous creations at the exhibition in KL. — Photos: LOW LAY PHON/The Star

Roziah and one of her gorgeous creations at the exhibition in KL. — Photos: LOW LAY PHON/The Star

Family project: (From left) Zaitun, Julitah, Julia and Narty with their artwork The Tukad Kad Sequence.

Family project: (From left) Zaitun, Julitah, Julia and Narty with their artwork The Tukad Kad Sequence. -- LOW LAY PHON/The Star