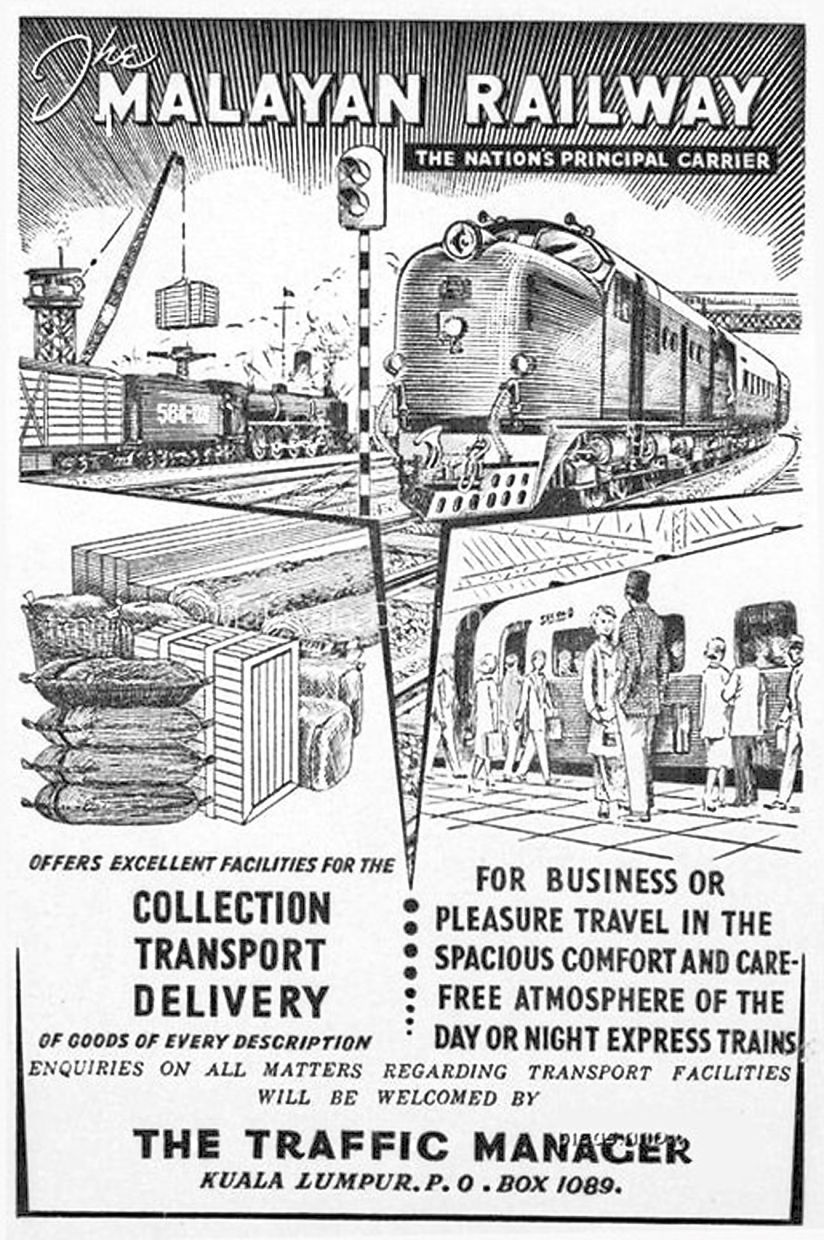

Part of an old advertisement for Malayan Railway. — Photos: Handout

You stumble across a set of old, faded advertisements for the Malayan Railway tucked away in a musty corner of a street-side bookshop in Kuala Lumpur. The bold graphics, the allure of distant journeys, the promise of exotic destinations – images that capture a bygone era when steam ruled, tracks connected the unconnected, and the whole world seemed just a train ride away.

But behind these glossy advertisements lies a grittier tale, not of travel and commerce, but of sweat, toil, and lives spent laying down the very tracks that would define Malaya’s economic landscape.

Imagine the scene: The relentless tropical sun, the incessant chirp of cicadas, the air thick with humidity and the cacophony of a thousand hammers striking metal. Here, deep in the jungles and along the burgeoning towns of the early 20th century Malaya, Indian labourers are the lifeblood of the railway’s expansion. They are far from the adventurism and romance promised in travel posters; they are the unsung, the overlooked, the pillars upon which the colonial economy rests.

The Indian labourers, drawn from the parched villages of Tamil Nadu and the lush fields of Kerala, were promised betterment but received bondage. Their days were marathons of hardship – clearing dense forests, laying heavy tracks, all under the watchful eyes of overseers whose interests lay in deadlines and profits, not human lives.

Tragically, during the construction of projects like the infamous Death Railway (Siam-Burma Railway) in neighbouring countries during the Japanese occupation, an estimated 45,000 workers perished under the harsh conditions of forced labour, disease, and sheer exhaustion from the relentless workload.

Parallel to this, the Ceylonese community, brought over for their clerical acumen, found themselves navigating the complex hierarchies of the colonial administration. They manned the stations, kept the books, and ensured the trains ran on time. Places like Little Jaffna in Brickfields, Kuala Lumpur and Jalan Ceylon in Penang became cultural beacons, centres where a slice of Sri Lankan life thrived amidst the Malayan backdrop.

And then there’s the culinary tale – how the railway canteens, often run by the wives and families of these labourers, became melting pots of culture. The aroma of freshly made tamarind rice, the sizzle of spicy curries – these flavours provided a brief but powerful reminder of home, of distant lands left behind in the pursuit of survival.

This is the real story of the Malayan Railway. Not just a tale of economic ambition and colonial expansion, but a saga of resilience and contribution. A story where every sleeper laid and every track bolted down speaks of the toil of those who, despite the odds, laid the foundations of modern Malaysia.

In the end, what remains is a legacy – etched not just in the steel tracks that criss-cross the peninsula but in the enduring spirit of those who built them. It’s a legacy that challenges us to look beyond the romance of old travel posters, to the real stories that they mask.

This is a narrative that demands remembrance and respect, for it’s built not just on the aspirations of an empire, but on the backs of those who truly made it possible.

The views expressed here are entirely the writer’s own.

Abbi Kanthasamy blends his expertise as an entrepreneur with his passion for photography and travel. For more of his work, visit www.abbiphotography.com.

Malayan Railway ads

Part of an old advertisement for Malayan Railway. — Photos: Handout

Old advertisements for Malayan Railway. — Photos: Handout

d4935d21d13e95e029ebf09500e29ef1

a135103d7b4a368ebba51e33959dce19

e0dc6a1ac0b24bbbcc258f9bc74db322

68510a52e0743acb2a371eb761db697e

db49a9986fc32aa64242cb6015b36273