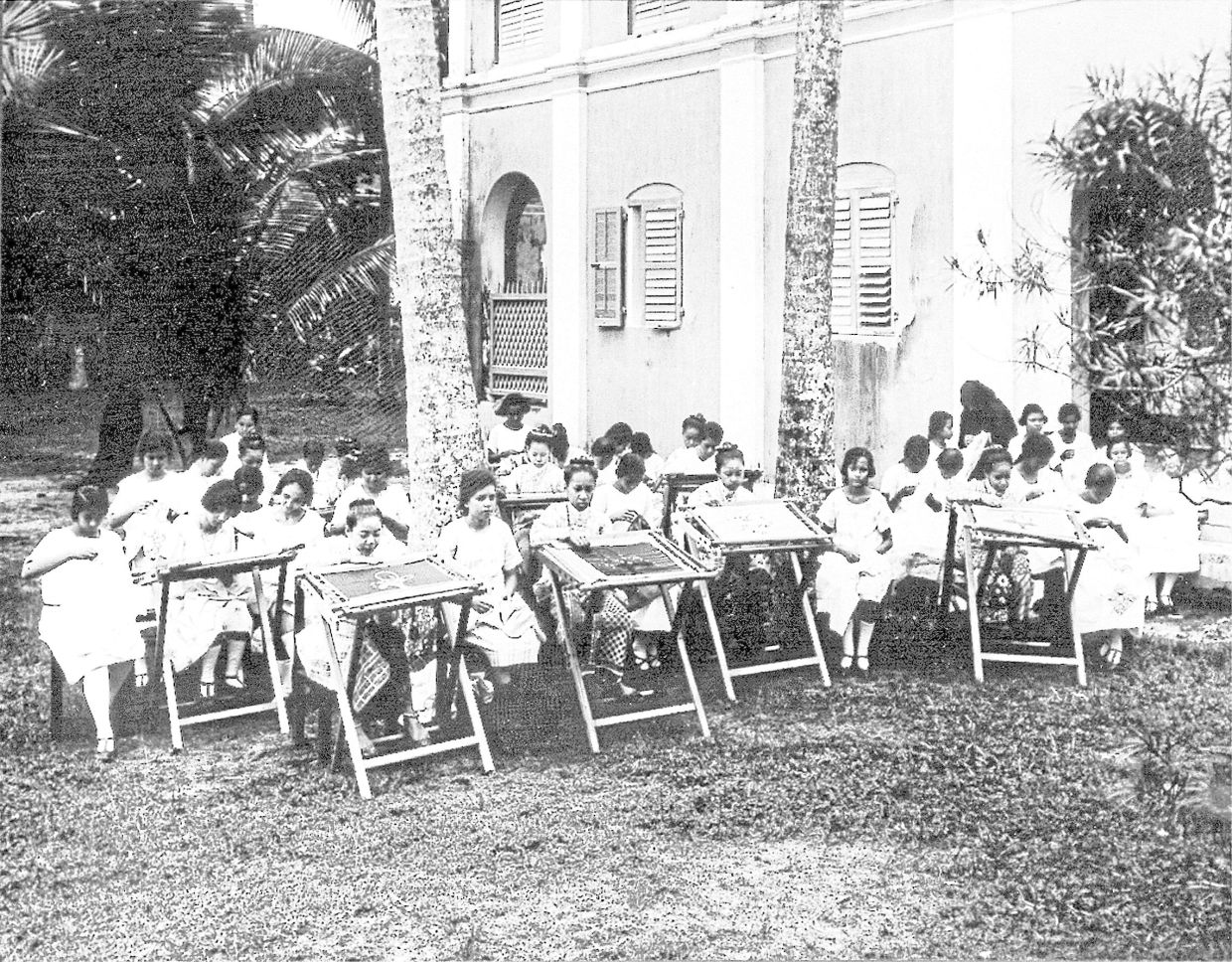

Long legacy: SK Convent Light Street in George Town not only provided schooling for Malaysia’s children but also Thai elites in the early 20th century. — Filepic/The Star

IT had been an enlightening trip into predominantly Buddhist Thailand as part of my following on the trail of the Catholic St Maur Sisters in their education missions in Asia beginning from the mid-19th century.

Commencing at Bangkok, I travelled to the northern and southern parts of the country where the sisters cleared jungle to build their schools and progressively expanded them in size and facilities for modern learning.

Presently called the Infant Jesus Sisters (IJS), they graciously accommodated me at their convents and made arrangements for travelling about and visits to their schools and an impoverished community they assist.

In Bangkok, the sisters took me through streets choked with traffic jams – as expected – and we walked in hot weather to places where their predecessors once served at intermittent periods for more than a century.

On the grounds of the Holy Rosary or Kalawar Church situated by the Chao Phraya River in Samphathawong District – with Chinatown at its heart – a pioneer team of sisters sent from Singapore established their first school in 1885.

In sync with the name of the church originally built by Portuguese missionaries, it was called Rosario Convent School but it later moved to Convent Road in Silom, which at present time has developed into a major commercial centre.

Another school was opened and expanded quickly but a deadly epidemic dealt a cruel blow to the sisters, yet again – just like the way it had often happened in Malaya, Singapore, and Japan.

Four sisters who died were buried in a single grave, and with their schools closed in 1907, the remaining survivors were directed to Ipoh as a new convent was being opened there.

But the sisters’ schools and teaching services, particularly in English, were very much needed, so where did the young girls get their English education then?

The rich and elite, including royalty, enrolled their daughters at Convent Light Street in George Town for the sisters’ famous brand of wholesome education, which also included courses of grooming in a finishing school.

In the days when air travel was limited, the young ladies would usually embark on a southbound train from Bangkok to the border town of Padang Besar in Perlis, ride the length of Kedah state and reach Butter-worth or Bukit Mertajam in mainland Penang before crossing over to Penang Island by ferry.

The Second World War and Japanese Occupation of Malaya put a halt to this arrangement but it resumed when the war was over and better days returned.

Then came the surge in demand for schooling by Malayan children, and so the situation faced by Convent Light Street and the needs of Thai students spilled over to other convent schools on the island.

Soon the Penang convents, which by then were called Convents of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ), were reserving places for locals only and the Thais were deprived of their English education.

Meanwhile, a prominent Thai teaching sister was taking up duties at the main convent and she was none other than the princess who was educated, trained as a teacher, and made her religious profession in the days not long after the Japanese arrived.

Sister Marie Jombunud who carried the royal title of Mom Rajawong Foophol, was the great-granddaughter of King Rama III and daughter of Prince Chonjarem Jombunud.

She taught in Penang from 1947 to 1956 before being transferred to Singapore’s St Theresa’s Convent as principal, returning to Thailand in 1970, thereafter serving in several senior positions including in a provincial capacity.

The lack of places for Thai students in Penang led to the re-establishment of Thailand’s own convent schools – Mary Immaculate Convent at Chonburi in 1957 and Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ) School in Bangkok in 1963.

CHIJ School provided commercial classes, particularly private secretarial courses in the English medium, and also functioned as a finishing school for girls.

Other schools then followed, including those in poorer areas in the northern parts of the country, in line with the sisters’ founding objective of providing education and help to the poor and unfortunate.

At Khon Kaen province in the north-east, the convents are inspiring examples of how the sisters had the foresight to acquire jungle land and, with sheer grit, convert them progressively into fine education centres for young children.

Here, I visited the convent communities and schools at Khon Kaen city and the towns of Nonsomboon and Banphai.

The school at Nonsomboon originally provided education for children of leprosy victims. It began as a gathering of children under a tree before they had a roof over their heads in a wooden hut. This setting later improved into stronger structures.

I was particularly impressed by the beauty of all the schools I visited, being the typical well- maintained convents I once knew – light pleasant colours, clean, neat, and surrounded by greenery.

These remain much the same way as the early sisters have operated them, staying private in ownership, and the sisters remain in full charge of all functions, including the academic curriculum.

In the process of interaction, I discovered some curiosities about the happy-spirited nuns; they know many Malaysian words and expressions, including the forbidden “rojak ” languages in school!

Jokingly, they have classified themselves as “made in Malaysia” and “made in Thailand”. The members of the former group especially knew about the once small town of BM, or Bukit Mertajam, because that was where their train journey into Malaysia ended.

Presently ranging in age from 70 to 101, they are mainly “made in Malaysia”.

They went through their religious development and training at the novitiate in Convent Light Street and later, some went to Cheras Convent in Kuala Lumpur when the novi-tiate moved there in the 1960s.

IJS Thailand was initially under the Penang Provincialate but it later expanded to become a province of its own and began its novitiate in 1971.

My trip concluded with Chonburi Convent in the south of Thailand, and the last on the itinerary was a visit to the Catholic cemetery, which is designated as the final resting place of the sisters.

I saw, among the uniformly simple white marble slabs and crosses, the single grave that is shared by the four early sisters whose remains have been exhumed and transferred here from Silom, and another which interred the princess-nun Sister Marie Jombunud.

Chen Yen Ling is the author of Lessons From My School: The Journey of the French Nuns And Their Convent Schools and continues her research into the intrepid sisters’ enduring education ventures from Malaysia to Singapore, Japan, and Thailand.