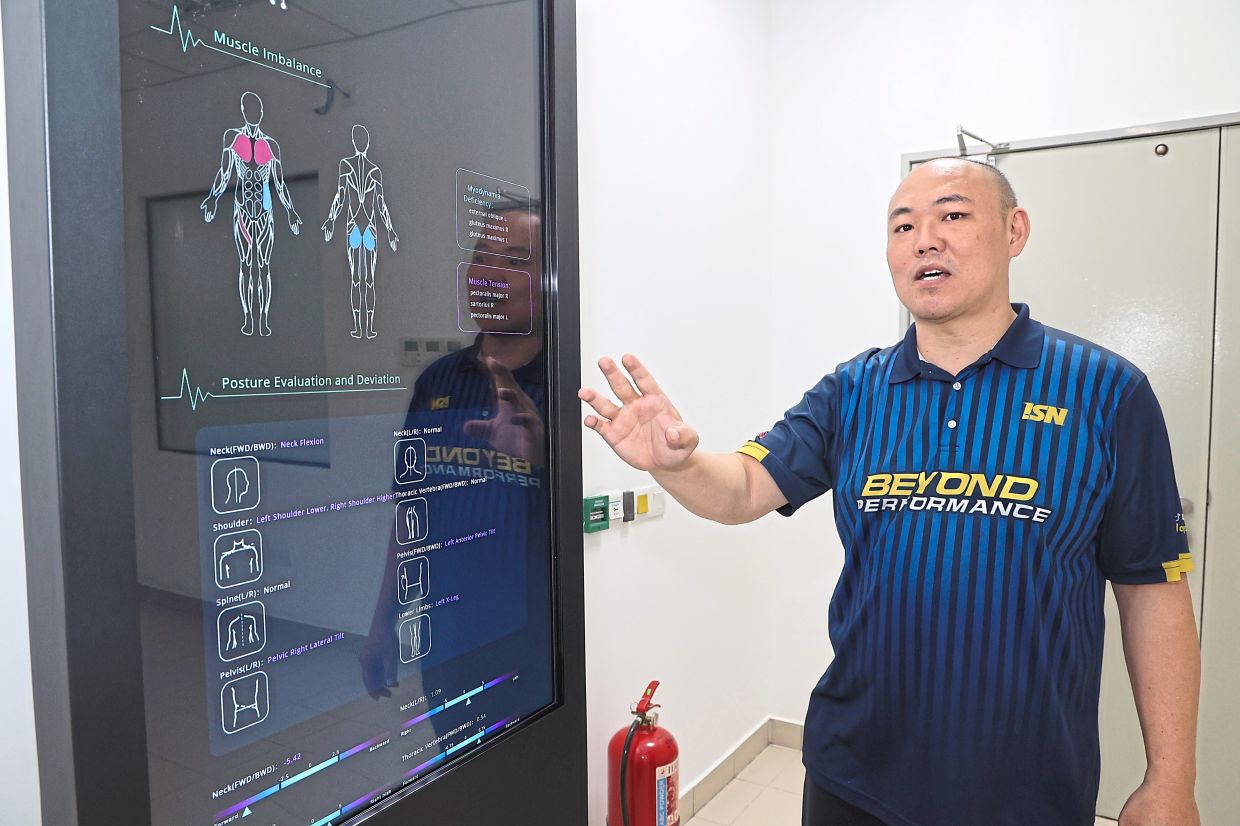

Dr Ler demonstrating the SMARTfit system, which allows scalable training designed to address multiple brain domains while igniting improved performance of the brain and body connection. — Photos: The Star

THE HoloMotion device looks like any touch screen directory in a shopping mall as it sits in a nondescript room at the National Sports Institute’s (ISN) project laboratory.

Roughly 2m tall with a large screen and packed with artificial intelligence (AI) features, it may be the precursor to the evolving Malaysian sports science gaining steam with AI-based approaches to performance analyses.

The device’s internal gadgetry was developed years ago in China but ISN has the only one of its kind in Malaysia after receiving it in June this year.

It takes just five minutes for an athlete to perform several agility movements – including bending the head forward and backwards and squats – while HoloMotion scans him/her.

The HoloMotion immediately compiles a detailed profile of the athlete, complete with injury risks for specific body parts and which movements are weaker, before e-mailing a list of exercises to address them.

With this device and others, ISN head of research translation Dr Thung Jin Seng plans to build a fitness and risk-of-injury profile of over 600 national athletes under training in a given year.

Thung says sports performance analysis in Malaysia is now still “tedious and labour intensive”, requiring constant video watching to analyse athlete performances.

“AI will help by giving more reliable analyses, much faster than what humans can do, and make the process much less labour intensive,” Thung tells Sunday Star about the AI in performance analysis that ISN has started to use.

The detail that HoloMotion manages to accumulate in five minutes could take a week for a human to compile, he explains.

Another technology being tested currently, that will be paired with the HoloMotion machine, is tensiomyography (TMG). This noninvasive technique measures how muscles contract in response to an electrical stimulus.

In athletes, it can detect muscle stiffness or its explosiveness, and monitor muscle recovery. It is used in sports medicine, rehabilitation, and physiotherapy to help prevent injuries, enhance performance, and monitor muscle function.

“You want the muscle to be bigger so that you have a bigger engine for that movement. We want to build a full profile of the athlete with myography. But doing it traditionally is time-consuming and tedious,” says Thung.

Pairing AI-based devices like HoloMotion with TMG, ISN aims to build a comprehensive injury risk profile for up to 700 national athletes being managed by the government.

“We want this research to produce a set of variables to predict injuries, using AI,” says Thung. “We will create algorithms of the exercise risk.”

HoloMotion’s AI feedback will be verified by using the Xsens 3D motion-tracking technology. Akin to movie-making’s motion capture technology, it gives real-time feedback on a subject’s biomechanical movements for better insights into injury prevention and quality of movements of athletes recovering from injury.

This research and its pilot project would be done in collaboration with several public universities, with Thung noting that partners may include Tunku Abdul Rahman Universiti of Management and Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris, and Universiti Malaya.

Predicting injuries will be key to drastically reducing risks of injury to athletes, shortening recovery times, and using the time saved to get faster, stronger, and more skilful. And, hopefully, will culminate in Malaysia’s first Olympic gold in the Los Angeles Games in 2028.

Thung says ISN’s project was started this year and will be a four-year project until 2027.

He also believes that similar technology must be used in talent identification to find Malaysia’s next crop of potential medal winners earlier.

“Myography is used overseas, such as in Germany, on children as young as three years old but doing so would need wider acceptance in Malaysia,” he says, adding that not many parents would agree to subject their children to electrodes for a tensiomyography examination.

In Germany, “They test children as young as three years before any training or intervention is done to them. That is the best time to identify talent and pick the best athletes and train them,” he explains.

ISN’s efforts are emblematic of greater sophistication in sports science in Malaysia, although the results would only still trickle in over the years, say sport scientists.

Better sports performance still needs a holistic merging of more fields of study, particularly in sports science, computer science, information technology, and engineering.

All of these must be geared towards AI development, Thung points out.

On the education front, the Tunku Abdul Rahman Universiti of Management and Technology (TAR UMT) Sports Coaching and Performance Analysis degree programme is a pioneer in upping the stakes in teaching performance analysis to budding sports scientists.

The programme, launched two years ago, has invested in equipment that will help undergraduates adopt a scientific approach towards enhancing sports skills relevant to sports coaching to improve sporting performance, sports skills, sporting tactics, and technical effectiveness using performance analysis.

Students have begun using more sophisticated equipment such as the SMARTfit system from California to measure reflexes and motor skills and the Bod Pod, an egg-shaped device that measures athletes’ weight and volume to determine their body density and calculate body fat percentages.

TAR UMT deputy dean (research and development) for applied sciences Prof Dr Ler Hui Yin says the programme was inspired by 2016 working visits to China and South Korea in 2016 to observe their approaches to performance analysis.

“Real-time analysis was everywhere at the Korean National Sports institution, with video cams and computers in a big room, and coaches working with iPads.

“We realised that we were missing a lot, that we could incorporate a lot of knowledge from countries strong in sports and do what they were doing.”

“Performance analysis has advanced far past video recording and watching,” says Ler.

Using badminton, for example, she says today it is not enough to look at a match’s recording and point out athletes’ mistakes.

“If there are no stats or information about what caused errors or mistakes, it’s not enough,” she says.

“To give constructive feedback to athletes, you need to give data and tell them. Cannot just point out the mistakes.”

It’s demotivating to keep pointing out mistakes.

“You don’t have to be a psychologist to know that you don’t just tell the errors and not how to look into addressing them.”

Koh Weat Teck, a TAR UMT masters postgrad in sports and exercise science, says the next generation of sports scientists to which he belongs needs to “sell” the benefits of the science first to coaches.

The principle remains to collect more data to detect trends and help the coaches determine how much load the players are taking on, Koh says.

“Sports technology is good but sports science is a conceptual thing. Even without the equipment, it’s important to apply the science.

“Using sports tech in high performance, recently we started engaging with more technology, like in the data we collect.

“But the key thing is how to make sense of data and give insights to coaches.

“The players have to benefit from it or else we are collecting data for the sake of collecting. If the players can’t benefit, the coaches won’t either, and we will be working in silo and further away from each other.”

But most coaches today are still thinking of volume, he notes.

“Train more, run more is still the thinking today. But what do you really need? Why run 20 rounds when my routine is just 90 seconds?

“Art of coaching is blending science and using the coach word to sell it to other coaches,” says Koh.