MANY governments all over the world have their own social protection programmes to alleviate hardships faced by their citizens, notably those from the lower and middle-income groups. Some examples of these social protection programmes are direct cash transfers, price control ceilings for essential goods, subsidies for fuel and electricity, and health and education sectors.

In Malaysia, subsidies have been part and parcel of the economy for many years, so much so the rakyat expects the government to continue providing them. The rakyat have become accustomed to subsidised services and products. It’s as if subsidy has become an inalienable right.

As the government grapples with getting its finances right, trying to balance its revenue and expenditure, there have been calls for the current subsidy system to be reformed. One of the key reforms is to move away from the current costly blanket mechanism that benefits everyone, including high-income earners who are certainly not in need of any assistance, to a more targeted one which focuses on the needs of the low and middle-income groups.

This was indicated by Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim during the mid-term review of the 12th Malaysia Plan. Further details are expected to be announced during the Budget 2024 presentation on 13 October 2023.

Here are some questions and answers with Dr. Yeah Kim Leng, Professor of Economics and Director of Economic Studies Programme at Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia at Sunway University and Member of the Advisory Committee to Finance Minister (ACFIN) to provide a better understanding of the issues at hand:

1. How big is the subsidy bill in 2022 and what is the projected figure for 2023?

In Malaysia, the government has long subsidised basic goods and services. These subsidies are intended to lessen the burden on vulnerable groups. Among other things, they include subsidies for rice, flour, cooking oil, chicken and eggs, electricity, petrol, diesel, cooking gas (LPG), healthcare and education.

Subsidies do not actually make the cost of the items cheaper. What happens is the user only pays a fraction of the cost to purchase those items, while the rest is borne by the government. The portion that is borne by the government is what we refer to as subsidies.

Herein lies the problem. Our subsidy bill, which includes social assistance, has been growing over the years. If you can imagine, in 2008, our subsidy bill stood at RM35.2 billion. As of 2022, this had grown to RM67.4 billion. This is almost a two-fold increase.

Subsidies in 2022 accounted for nearly 4% of Malaysia’s gross domestic product (GDP) – the value of goods and services produced - and made up approximately 23% of the government’s operating expenditure. Basically, almost a quarter of allgovernment’s operating expenditure is used solely to provide discounts on some of the items the rakyat buys, rather than on things that may potentially be more productive for the nation.

We could also be using this on development expenditure, which is crucial for nation-building in economic and social development initiatives such as education, healthcare, social housing and public transport.

From another perspective, if we consider that the government’s revenue in 2022 was RM234 billion, subsidies consumed almost one-third of that. Thismeans, for every ringgit that the government collected, 30 sen went to subsidies.

The government has forecasted RM58.6 billion in subsidy payments for 2023. Despite being lower than the amount allocated for 2022, it is still a huge number.Needless to say, this isn’t sustainable.

2. Why can’t the government continue with what they have been doing for so many years and why it is no longer sustainable?

Let’s pause and take a hard look at our current financial position. The fact of the matter is Malaysia has been spending more than it earns in all but five years since 1970. That’s 48 years of deficits. Running a deficit budget means the government has to borrow. Hence, as at end 2022, the total government debt is RM1.08 trillion. And that’s excluding government guarantees provided to numerous government-owned entities, which if included would push the total government liabilities to almost RM1.5 trillion.

How big is RM1.5 trillion? The amount is equivalent to the size of the Malaysian economy. Or divide that by Malaysia’s population of 32 million, that’s equivalent to RM46,875 debt for each and every one of us.

Having a huge debt is a burden to the government’s financial position. In 2022, the cost to service government debt amounted to RM41.3 billion and exceeds what is spent on health, education, transport and housing put together. Moreover, nearly 30 percent of the interest payments ends up in foreign hands.

RM41.3 billion is also equivalent to 20% of tax revenue. In other words, for every ringgit that the government collects, 20 sen goes towards paying the interest on the debt alone. Paying interest is not productive as it doesn’t generate any spillover impact to the economy.

3. What are the big items that the government subsidises?

The government subsidises many goods and services. Our rice, which is being sold at RM2.60 per kg is among the lowest in Southeast Asia. A visit to the hospital will cost only RM1. Primary and secondary education are free for citizens. Studying a Bachelor in Medicine and Bachelor in Surgery (MBBS) degree in University Malaya will only cost RM 14,990 for the whole programme – among the lowest in the world, although it should be noted that this too is partially subsidised by the government.

If we extend this concept further into the realm of education, the government has also provided subsidy – although it is not called as such, in the form of Rancangan Makanan Tambahan (RMT), Bantuan Makanan Asrama, Bantuan Makanan Prasekolah, Skim Pinjaman Buku Teks, Bantuan Awal Persekolahan, Biasiswa Kecil Persekutuan to our children.

These are just some examples. The actual list of subsidised goods and services would be even longer.However, these subsidies don’t account for the majority of our overall subsidy bill.

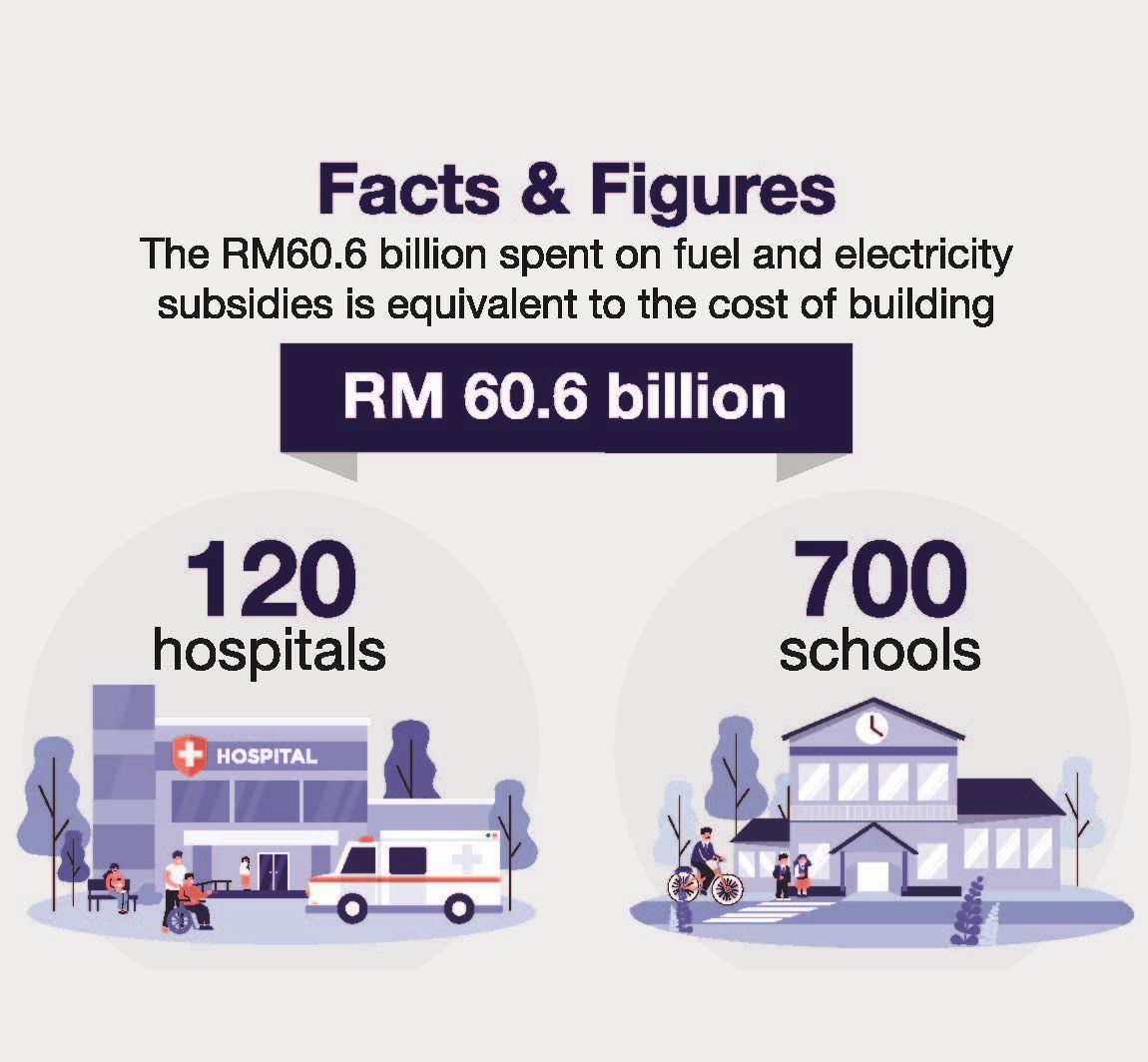

The biggest chunk of our subsidy expenditure comes from fuel and electricity subsidies. Together, these two items accounted for RM60.6 billion, or over 90%, of the total subsidy bill. Our subsidies for fuel (diesel, petrol and cooking gas) alone came up to about RM50.8 billion (or 77%), while our electricity subsidy amounted to RM9.8 billion (or 14.8%). What does this mean for the rakyat?

Put it this way: with RM60.6 billion, the government could potentially have built the equivalent of 700 schools or 120 hospitals per year. Try to imagine what a difference that would have to the country – especially those in rural areas.

This is the first part of the discussion on subsidies for the Rakyat. Continue with the second part here.