Founded on the idea that humans are inefficient, the chain has closed 1,300 stores in three years and needs to adjust its model, experts say. — SCMP

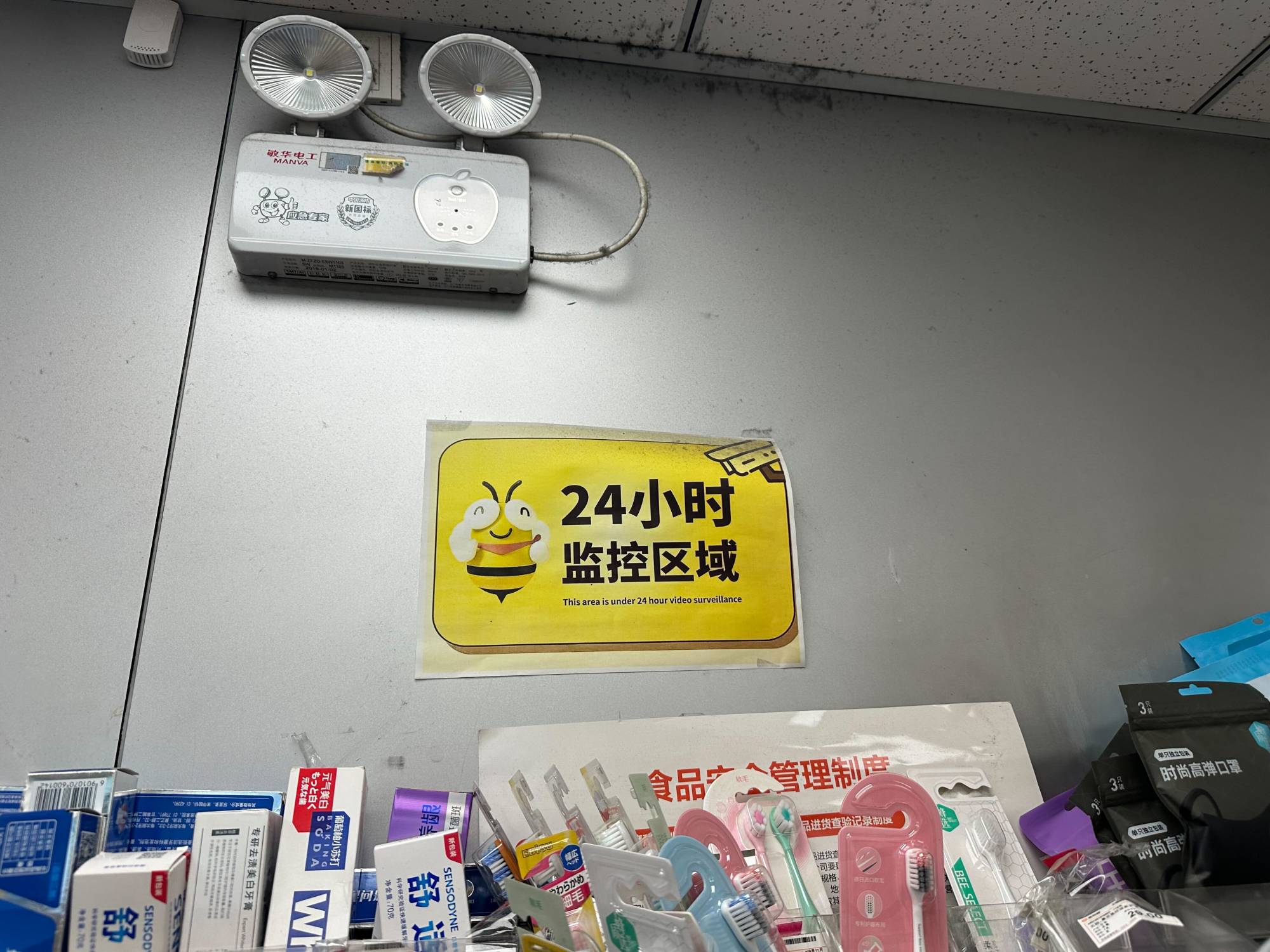

Step into a Bianlifeng convenience store in China, and the first thing you are likely to notice is a grey robot roaming among the shelves of snacks and drinks. Next you might note the high number of cameras on the ceiling and a sign advising you that the store is under 24-hour video surveillance.

The setting is emblematic of the company’s attempt to eradicate human decision-making from the operation of its stores. While the robot has no name, it does have the power to boss around the one or two humans on duty, and their pay depends on following its orders.

“Our unstaffed shop means that there are no people in the entire business decision-making process,” co-founder Zhuang Chenchao said in 2019. “We believe that every node that is manned leads to a decrease in overall efficiency.”

However, in 2024 the robot has come to symbolise the flaws in that belief. After growing quickly to 2,800 shops in 20 cities in 2021, Bianlifeng has closed 1,300 stores in the past three years and now serves only nine cities.

In that span, the company fell from 11th to 25th on the China Chain Store Management Association’s list of the top 100 convenience stores. And experts say the company must alter its approach to succeed in a competitive market.

Founded in Beijing in 2017 by Zhuang and Wang Zi, Bianlifeng applies a rating system to employee performance, and cuts their pay if scores are too low. The robot and cameras monitor employees, as well as the consumption patterns of customers.

When asked how the robot helps operate the store, a clerk from Beijing who declined to give his name said, “It does not even have hands – the only thing it can do is to deduce our scores.”

The company’s approach feeds data on product variety, selling prices, traffic flow, cargo loss rates and customer preferences into algorithms that optimise operations, making it easier to replicate the operating model across shops, according to Zhuang.

However, disputes have arisen as employees and franchisees report being “trapped” in the rigid management system. Employees suffer from high pressure and what they say are unreasonable assignments, while franchisees argue that they miss out on profits due to the system’s tight grip on store operations.

“Algorithms cannot completely replace human agency,” said Jason Yu, general manager of market-research firm Kantar Worldpanel Greater China and vice executive president of CTR Media Convergence Institute. “How to combine human touch with its management will be a challenge for Bianlifeng.”

The company’s “narrative of AI-driven convenience stores was created when venture capitalists’ hot money fuelled China’s consumer market,” said Yaling Jiang, the founder of ApertureChina, a consumer-centric consultancy. “It was created for an IPO, reflecting the founder’s belief that human workers are inefficient.”

The problem is that the in-store management decisions are made based on past data, which fails to reflect or forecast what consumers actually want, Jiang said.

Another reason for Bianlifeng’s difficulty may be its failure to embrace franchising until recently. This model was suitable for its initial operations in large cities like Beijing, targeting white-collar consumers. But as it attempted to expand into second and third-tier cities, it faced challenges from more localised franchises as well as community markets, analysts said.

“Whether Bianlifeng’s direct-sale model can be replicated in other cities remains a question,” Yu said. “The overall environment of convenience stores in those places is different. With a franchise model rather than direct sale, the company can utilise the advantages of local franchisees who are more familiar with local communities.”

Overall, Chinese convenience stores are struggling with a decrease in spending per person. While the average daily number of customers increased slightly from 344 in 2022 to 346 in 2023, the average spending dropped 21% to 21.5 yuan, according to a KPMG report.

According to the National Statistical Office, consumption in the country’s four tier-one cities – Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen – in the first half of 2024 grew more slowly than it did nationally.

“Economic consumption is a bit weaker in the first-tier cities compared with second- to third-tier cities,” said Kou Yuanyuan, senior analyst of the equity research department of Haitong International Research.

That translates to opportunity for convenience stores, which are not distributed evenly across China.

“Among the largest cities, the density is high, yet in smaller cities and the countryside, the density is still low,” Kou said. “There’s a large potential market.”

Operators have been responding. Stores focusing on business areas made up around 36.1% of the convenience stores in 2022, but this declined to 21.3% in 2023, showing a declining contribution from white-collar customers, according to the KPMG report.

Aware of this trend, Bianlifeng began a project to grow franchising in late 2023. However, whether this tactic will restore its past glory remains uncertain.

“Bianlifeng is competing with other more popular franchises like Lawson, Family Mart, C-Store, and 7-Eleven, and based on third-party reports, it charges (franchisees) a lot more,” Jiang said. “It does not have a strong brand, and in this case, their narrative of AI-driven and big data is a premium that potential franchisees do not feel the need to pay.”

Big data can be a powerful tool for operational factors like inventory management, but it is important to “let it assist, instead of driving decisions like what Bianlifeng is doing”, Jiang said.

“They need to embrace technology but simultaneously incentivise human ability,” Yu said. – South China Morning Post